Head to the AP Shop to grab a copy of NEGATIVES: A Photographic Archive of Emo (1996-2006)

From its aggressive sound to the subversive style, every anarchistic facet of punk rock has been built on a foundation of tenacious drive and a do-it-yourself attitude. And Amy Fleisher Madden’s story is one that encapsulates the spirit of the subculture she has championed perfectly. From the moment she asked a friend what the Fugazi sticker on her lunchbox meant, her journey into “the scene” was set in motion — one that would swiftly take over her teenage life, and lead her to become not only one of the few bookers in the country for punk and ska bands, but also to start Fiddler, her own record label, by age 16, which would break bands such as New Found Glory, Dashboard Confessional, Recover and more.

Read more: What does emo really mean? The story of the genre in 11 songs

For any of us who dipped our toes in the scene, or wound up in its very center wearing a pair of thigh-high Docs, we had our own lunch box sticker moment. Whether it was that song or this band, a show or a T-shirt, it fell a set of dominoes and led us to where we are today, with a brain full of Braid lyrics, eagerly awaiting the enigma that is the next My Chem album.

If we were in the scene’s trenches like Amy, or enjoyed it from afar, we were part of a tight-knit community that made up what is now considered the second and third waves of “emo.” We were, heard, and felt the punk misfits who wanted to push the envelope with lyricism loaded with an emotionality the genre hadn’t yet held space for. There was a closeness and a friendship that was felt through the vulnerability of punk and emo in this era that is evident in the music itself and now, all the more evident through Amy’s book NEGATIVES.

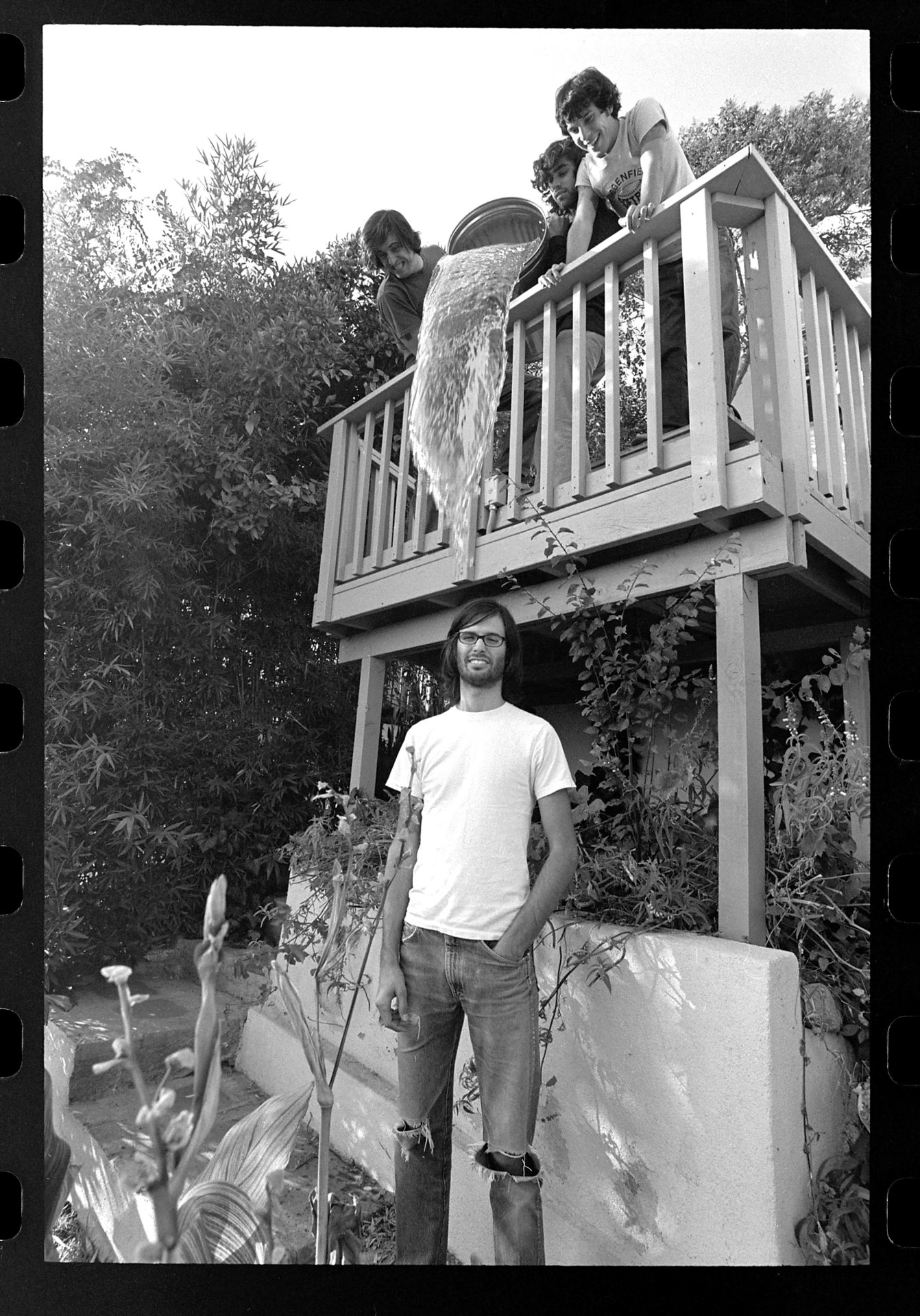

Over the last three years, Amy has been pouring over an archive of intimate, rare, and never-before-seen images that offer insight into the scene from 1996-2006. The book is a beautiful window into what was not only a successful time in the alternative music scene, but an honest and powerful period of friendship and community building in the ever-evolving punk genre, and the iteration that would later be coined “emo.” Featuring favorites from the second wave of emo such as Sunny Day Real Estate to the third wave’s Jimmy Eat World, alongside essays and contributions from artists like My Chemical Romance’s Frank Iero, Dashboard Confessional’s Chris Carrabba, and Thursday’s Geoff Rickly, Amy has unpacked an unruly and important time in music with remarkable dedication.

We sat down with Amy to talk about how she found her way from a Latin Jazz club in Miami to breaking some of alternative music’s biggest bands, the process of putting together the ultimate emo book, and the story of her first time seeing Thursday — which of course includes streaking and an abandoned barn.

Congratulations on your book. How long have you been working on it?

Three… or 25 years. Whatever you want to consider. I started it before the pandemic and then before I even knew what it was. At that time, it was moving towards being a documentary — I had a documentary team, a producer, and we had a couple of meetings, and then the shutdown [happened]. I have a problem admitting defeat and was like, “We can still do this.” Once we started Zooming, though, I just had this heartbreaking feeling where I was like, “I don’t want to do it like this. I don’t want to interview bands over Zoom.” You have to feel it. You have to be in it. So I put it away, put it in a drawer for a couple months, and then realized, “I think it’s a book.” I was pretty hell-bent on not writing anything for a little while because of the brain power that it takes, and I wasn’t sure that I could do it. But then I just started doing it, and I was like, “I can do this.” And it became a book. So three-ish years, really.

In my experience, it takes less brain power when you care deeply about what you’re writing.

Yeah. It tends to spill out easier.

So, speaking to publication, you started it all off with a fanzine, correct?

Oh, my gosh, yes. When I was really young, high school! I was 16. There’s probably a hundred of them in existence — it was called Fiddler Jones. The zine morphed into my label, which was still when I was in high school. And that’s how I got my start in music.

Which music scene did you make an entry through?

I was born and raised in Miami, Florida, which is not known for its cool punk-rock scene. Latin jazz and fishing were very much a part of my life — and Cuban food is my favorite food. But there was this little tiny all-ages venue, literally right outside my neighborhood. My parents’ neighborhood backed up to a really big street called U.S. 1, which is the main road. And if you crossed over, there was a Latin jazz bar named Cheers. But the owner of the club wanted to start branching out into different kinds of music — she was a lesbian, and she started out by doing a gay night, and then a rock night and a local band night. So, some of my friends played a “local show,” and I went there and I had my zine with me and I met her, and she took me under her wing 100%. At one point, she was like, “Why don’t you do the local show? I don’t know anything about this.” I was 16, but I sort of tricked her into signing off on all this paperwork for me for school. I made it an “internship.” I got to leave school early to go work at the all-ages gay bar. And she really showed me the roads about it.

To backtrack, how did you initially get drawn into the scene? What was your first exposure to punk music?

My best friend in high school, her name is Jessie, we are still BFFs, so this is mid-’90s, and she was one of the cooler people that knew about mail-order catalogs, ordering merch, and records and things. I’ll never forget it. She brought a lunchbox to school in high school, which was very cool, and she had a big Fugazi sticker on the lunchbox. I remember the first day we met at school, I was like, “What is Fugazi?” And she’s like, “It’s a band. You probably won’t like it.” [Laughs.] And she went on to show me a lot of really cool bands. From there, we made more friends in high school just that way, finding the couple other [punk] kids, and somebody who was really into Operation Ivy.

How were you finding these emerging bands to book at the venue?

The local bands were super easy because in Miami, there were so few of us that were into punk things, and you were kind of by default also into skateboard culture. So at this point, if you had baggy pants, we were friends. If you saw somebody wearing a band shirt, that would be a flag. You would just walk over them, be like, “Hey, you like bands? I like bands.” So I met a lot of local bands, high school-age people. And then, through working at Cheers. Things were so small back then. There were so few booking agents — and I still remember Stormy Shepherd, she booked all the Fat Records and Epitaph bands, and she literally would just call Cheers on the telephone and be like, “Hi, I got these bands coming through.” They would send a press kit in the mail with an 8-by-10 glossy photo of the band. And you just book the band. It sounds very simple when I’m telling it, but there were so few of us, it was probably a hundred people in the country Max making these calls. Everybody knew everybody back then.

At what point did you decide to start the record label?

So the first really big show that I had at Cheers was also at a time where ska was having a big moment — and Less Than Jake was one of the biggest bands, because they were merch kings. I remember I booked a Less Than Jake show, I made $150. It was big vibes. I just remember sitting there and thinking about it, like, “Well, if I book 10 big shows, that’s well over a thousand dollars, and what could I do with that?” I just loved everything so much. I wanted to put money back into it. And from knowing all of the high school bands who didn’t have any attention from record labels or enough money to press their own records, I spent the money pressing a seven-inch. And the first band that I pressed the seven-inch for was Chris Carrabba’s first band, the Vacant Andys.

How did you meet Chris?

Those guys lived an hour north of me in a city called Boca. Those guys were a couple years older than me, and they lived a little far away. But when I met them, I booked a show for them, and I just loved them instantly. That was the first record I did, and it was wildly unsuccessful. [Laughs.] I didn’t really factor in that. Let’s say on a big day, 300 people would go to a show in South Florida. That would be a big moment. But I pressed 500 records. And it was like, “Well, I sold 30!” It was a big learning curve, of course.

Wow. Well, you aren’t doing the label anymore. What was the point at which you decided to stop?

I had my label from ‘96 to 2006, which I just realized is hilarious because that’s the era of my book. Throughout the time of the label, I had been in and out of college. I would go to school, and then a band would get big, and I would take a leave of absence to pay attention to that. Then I would run back and be like, “OK, I have to finish college.”

After some time doing this at University of Miami, everything changed scene-wise. All the venues closed, and everybody got older. The bands that I was working with started touring. So I got a job in LA, and I moved to Los Angeles. After a little while, I applied and enrolled in a school in Pasadena called Art Center. I only withdrew from Art Center twice! But finally, I closed the label and told myself I’m going to finish this degree so I can be a real adult and be a functioning member of society.

What was your relationship with that scene after you closed the label?

It went dormant for me. I definitely felt like I needed to take a break. I felt like by being involved in music, part of me was arrested development, where it was like, “OK, I’ve toured with bands and done all this cool stuff, but I haven’t paid attention to normal life things.” I had a company, but I would look at people that were my age that had a traditional life trajectory, and I’d be like, “Everybody is married and has jobs and has purchased homes, and I’m a loser.” [Laughs.] So I took a break from music for probably two or three years while I was deep into Art Center. It was super weird because people at school would come into class wearing band shirts that I had made, and I would just be sitting there like, “Cool shirt, bro.”

However dated and irrelevant the concept of genre is, it seems like a label that often gets attached after the fact in a moment of musical movements. In your experience, in the “emo” world, during the second and third waves captured in your book, what were you referring to it as at the time — punk?

Here’s the thing, and this is what the whole book is about. When my label was forming and the bands I was working with were coming up, we never called ourselves emo.

Don’t think anyone wants to call themselves emo.

No, I never uttered the word ever. I never put it in a press release. I never put it as a point of pride. It was almost a joke. I would say punk rock or indie rock to try to explain things to people. And it’s really interesting because after I graduated from Art Center, I got a job in New York, and when I got there, because I had taken so many breaks from college when I started my career, I was a good 10 years older than the people at my level. These people were using the word emo — and it wasn’t a derogatory term. It was really interesting getting acquainted with the word as a non-jab. Even still, I wrestle with the term, and obviously my book is a book of emo bands, but there is a little voice inside of me that was like, “It says emo on the cover — cringey!”

What is your experience with the current wave? What do you listen to?

It’s really hard. I’m trying not to fall victim to getting stuck listening to everything that was from my 20s. I’m trying not to do that actively, but I find myself liking more mainstreaming-type things. I’m obsessed with Phoebe Bridgers. There isn’t a day that goes by where I don’t listen to one of her records or a boygenius record. Then I’ll slip into comfort mode and be like, “Oh, I’m going to listen to a little bit of Sunny Day Real Estate.” I’m obsessed with Ruston Kelly — I’m not really a country person, but I think he calls himself “dirt emo.” I love Beach Bunny and Wet Leg — all of this really fun young people stuff. But then I do come home and slip into my sad people shit.

Can you share one story that’s not included in the book? Your first time meeting or seeing one of these artists live for the first time?

The best first memory of anyone in the book has to be the first time I saw Thursday. I was on tour with a band on my label, and the tour wasn’t going too well — and we were lost and driving around Kentucky and Tennessee, which is funny because I live in Tennessee now, and I called a friend to see if we could crash at his house in Lexington, Kentucky, but he told me to head to Louisville instead to try to jump on this house show that he heard about.

So, we drove to Louisville, and the show was on the second story of an abandoned farmhouse — I don’t even know how there was power. Someone must have brought a generator and a PA. I remember seeing Thursday, who I had been hearing about from other touring friends, and they were so all-encompassing, sonically, and spiritually — and in the middle of one of the songs someone from the crowd got completely naked and jumped out of a window that was behind the band. It was one of the craziest nights from that era of my life, and I’ll never forget it. The naked jumping person was fine — they landed on some hay.

After the show, I remember chatting with Geoff and Tucker, and we knew a lot of the same Jersey friends, and they were just so sweet and soft-spoken, the total opposite of how they were when they were playing, and I just knew the band was going to be so big. They were captivating to a room of 20 kids in an old barn — after that, I knew they were capable of doing anything they set their sights on.

What is your favorite image or page in the book?

I can’t really choose a single favorite image from the book. They’re all so important to me, and hard-won for different reasons. But one that’s special to me is the photo of Jimmy Eat World by Andy Mueller. This one hits different for me because I had this photo as a part of a poster on my wall in my room when I was still in high school. The poster was a promo mailer for their Static Prevails record on Capitol, and I just remember staring at that photo for years, wondering about what they were laughing about, and thinking what a great shot of a band it was. It was so rare to see a band so happy in their promo shot, and it honestly inspired me to take happier and more candid shots of my label’s bands when it came time to do promo shoots. Also, its lack of emphasis on Jim Adkins as the “lead singer” really set the tone for me when thinking about importance of band members within a band — they’re all equally important, individually, and as a whole — and this photo just felt like a crash course in emo photography ethics for me.