Welcome to Generation AP, a spotlight on emerging actors, writers, and creatives who are on the verge of taking over.

When glancing at Helena Eisenhart’s leather-clad, punk-infused designs, what you see doesn’t even scratch the surface of what truly lies behind each garment or accessory. The New York-based, independent designer always had an inclination toward the offbeat — “fitting in” just wasn’t in the cards for the multi-media creative because it wasn’t as fun anyway.

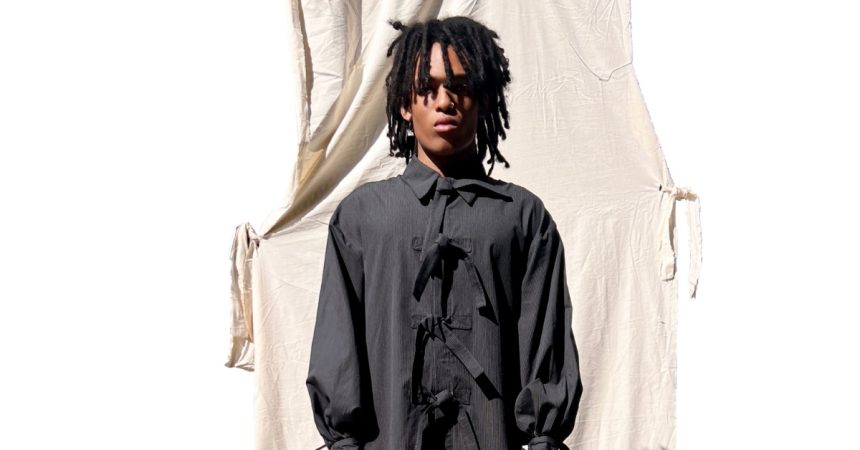

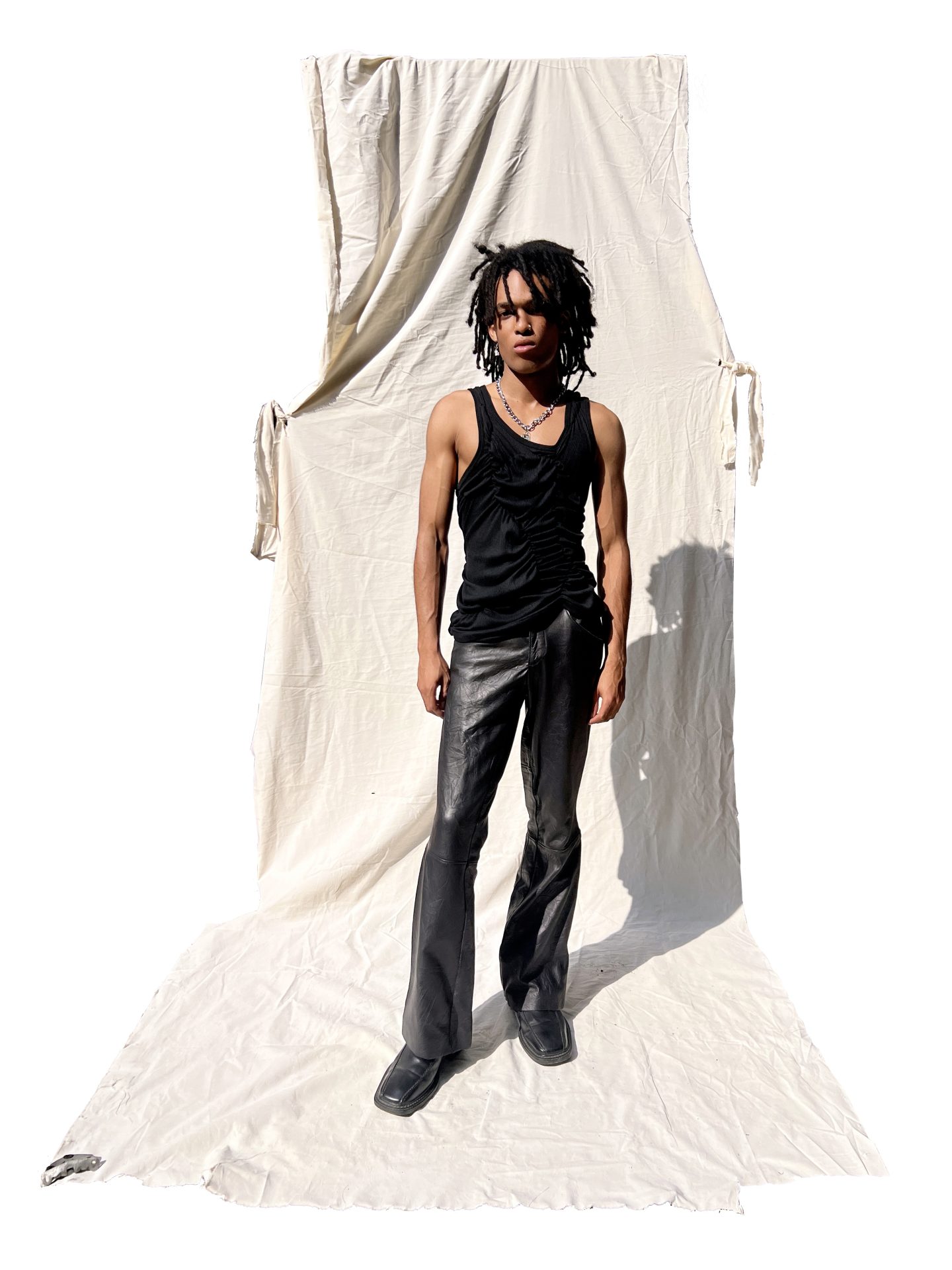

They began their namesake brand in 2015, fueled by a desire to create without confines and to tell stories through preloved, reworked garments, or found textiles. Eisenhart’s practice relies on a distinct creative synergy, a delicately balanced harmony between fine arts, fashion, and self-expression. All of these components have yielded one-of-a-kind pieces, such as a veil and gloves upcycled from a blood-stained wedding dress.

Read more: How Anna Sui created some of music’s most iconic looks

With looks created for Rico Nasty, SOPHIE, Dev Hynes, and more, as well as a solo New York Fashion Week exhibition under their belt, it seems like Eisenhart has truly found their niche. But they have labeled the brand as a “continuous exploration of identity” — both for themselves and for the wearers — signaling that there is still much more to come.

Alternative Press spoke to Eisenhart about their craft, their inspiration, and how their identity is inevitably interwoven into every upcycled creation.

You have a background in fine arts that eventually led you to fashion design. How did this new medium allow your creativity to flourish once you started experimenting with creating one-of-one garments through your brand?

I felt like I had been looking for a way to marry those mediums for such a long time. But around my graduation from school, I realized that garments don’t always have to be wearable, and sometimes you can think of them as sculpture. A lot of my initial garments were created from doodles, not even real full-blown sketches. When you look at my old sketchbooks, you can tell I come from more of an arts background. I had a professor who was a painter and also a designer, and she was super encouraging. Her name is Susan Cianciolo. She’s a great artist, and she’s still making clothes and art today, but she’s also a painting professor at Parsons and a design teacher at Pratt. I give a lot of credit to her because she really was able to find those students who felt a little bit lost, and she was able to hone their abilities. She opened me up to think, “No, it’s not a bad thing that I want to do all these things.” It’s actually a great thing.

You’re from the Bay Area but now create out of your studio in NYC. Typical East Coast versus West Coast style sensibilities differ in silhouette and “aesthetic.” How do you blend your upbringing with your current city setting through your craft?

Whenever I see my family, they’re always testing to see if I’m still a Californian. Maybe just ’cause I was a little bit emo. I always wore black. That’s just been my uniform, ever since middle school. But I think that’s actually very East Coast. A lot of people in San Francisco also really like all-black, but I grew up in the hippie suburbs. Everybody is bohemian and laid back. I had culture shock when I finally moved to New York because I noticed that people care about coordinating more here, like actually styling. I don’t think that’s a thing as much in the Bay Area. In Northern California, a lot of people say they don’t care about fashion, but anyone who says that just doesn’t understand what fashion is. Because saying that you don’t care is caring in a way. In New York, I definitely felt pressure to have a sense of style. And I think I now bring many elements of my style and these places to my process.

I feel like there’s this inherent sense of rebellion within your creations. To me, it sounds like that always existed within you, and now that still carries through with the brand.

I mean, I also love that hippie bohemian style, but I have to do it in my own way. I still feel like an outsider when I go back home. I’m always wearing something different than everybody else. It’s not even that I’m trying to do that — it’s just that I don’t like what everybody else is wearing.

Another core tenet of your process is using found textiles or found resources for your designs. Some of them are super unusual and unexpected. It’s so important for people to see designers like you creating from resources that you don’t typically expect to be used. What intrigued you about employing these textiles or resources in your process, and then what do you think wearers can learn from that inventive approach?

There was a lot of cool stuff at the thrift store growing up, but it wasn’t my size or wasn’t fitting the way that I wanted it to. So that’s where I started altering garments and figuring out how to sew. I also think because I was playing with lots of weird materials for my other art, I decided to add those in. I always mention when I knitted cassette tape for a look — that was a cool one. A lot of it also comes from not having any money and just using what I already had and creating my own textiles. I want to make somebody look at something and think, “What the fuck is that?” And I want it to be something that no one else can make.

But since my clothing has become more of a brand in the past few years, I’ve had to make things that are more wearable in order to sustain myself as a label. So to blend those worlds, I am working on putting together some art shows that incorporate original ideas. I’m also noticing a lot more designers who are using found materials becoming more mainstream, which I think is great because that means there will be more upcycled materials accessible to wider audiences. Typically, stuff like mushroom leather is so expensive and inaccessible to smaller designers. They only offer that to brands like Gucci and Chanel. You basically have to be invited to go to places like that — or create it yourself.

There’s this notion of accessibility that you mentioned that shows creatives or blossoming designers that it is possible to create using anything. It opens up space for a lot of people who may feel like there isn’t a place for them in this industry.

It’s a great exercise. That was something I even learned initially in school; we had a whole lesson about upcycling, but I wasn’t planning on becoming an upcycler. Those kinds of exercises were not only beneficial for learning how to be eco-friendly or sustainable but also for your own creativity. And it’s a good thing even just to practice at home. There’s a recent collection I created in 2021 that was all upcycled from the thrift store and antique stores in my neighborhood.

I think that the heart of upcycling is taking something old and imparting your own new perspective onto it. In your case, you do a really good job of connecting the old and the new. How do you feel that you honor each material’s past life while also telling a new story with your cutting-edge designs?

I tend to source my materials based on color or textile. Anything that is in poor condition and has holes or fraying, I’ll see if I can still use that part and add it to the garment somehow. I actually love showing the wear of a fabric if it’s not going to completely fall apart. I’ll end up using fabrics that I would’ve never normally used because I’m only using a small piece of it. Or maybe I’ll take that print and scan it, put it on Photoshop, and embroider it into the garment. And it’s not all garments that I’m upcycling — some of it is bedding, tablecloths, and kitchen towels. As long as it’s clean, then you’re good. A lot of those materials just end up becoming waste if I don’t recreate them.

Another element that imbues itself into your process and your work is your identity. You encourage a more fluid approach to identity. As you’re a nonbinary creator, how do you feel that weaves itself into your designs?

I think that when people see the clothes in person and try them on, most are happily surprised by how easily they fit. And not just because a lot of my pieces are oversized, but because I’ve taken time to make the patterns unisex. That’s another thing that’s become more popular, which is great. But I always think it’s so funny when you go to a store and you see “unisex” or “gender-neutral,” and it’s just a hoodie and sweatpants. A lot of things are just unisex without having to label them that way, like a button-up shirt. When creating certain pieces, you just have to pay attention to certain things about crotch length, shoulder width, and anything that is very specific to certain body shapes. I really enjoy opening up masculine and feminine styles and mixing them together. New York is always gonna be my home base for my brand no matter what because people here want to be weird. It’s cool to be weird here.

This ties into that rebellious outlook, going against the grain, and doing things the way that you want. What struggles have you faced in asserting your perspective and your way of production in an industry that can often be dictated by certain unspoken constructs?

Well, that’s a big question. I mean, even right now I’m getting orders from stores, and I’m struggling between balancing consignment and wholesale. When you go to school for fashion design or are self-taught, no one is really teaching you how to do business. Everyone that I’ve worked for, whether it’s a small designer or a big designer, has been pretty much self-taught about business. It’s such a learn-as-you-go kind of thing, and some people are following the fashion seasons in the very old-school traditional sense, and some aren’t. On top of honing my design, sketching, cutting, and sewing — it’s also about figuring out how you want to put yourself out there.

Tell me about your strangest, most idiosyncratic reworked design and how the concept came to be.

I don’t know if this is the weirdest, but this is still the coolest piece to me. I worked on an [oil-painted] dress with Tara Atefi in 2022. It was all upcycled from different Army sleeping bags, and that was so funny because I had to argue with the guy at my local thrift store about how much he was charging for Army bags. Tara did these crazy medieval-style oil paintings, and just learning how to do something like that with another person and collaborate is definitely one of the most artistic pieces, as of recently, that I have worked on.

Collaboration is another example of the creative synergy that you rely on in your practice, whether it’s you working with someone else or incorporating multiple different mediums into something that you’re working on. Who do you envision wearing and embracing the brand?

I always love the idea of a punk, downtown type of person like Lydia Lunch or Kembra Pfahler wearing my pieces. Somebody who’s more of a weirdo artist who loves wearing fun pieces. When I was a little kid, I always loved Karen O. I remember my dad sent me an article written about Karen O where she was wearing car parts onstage, and I thought that was so cool. I always envision a performer of some type, somebody who’s onstage, whether they’re a singer or an actor in a film. I would love to make costumes for a film or for ballet. I’ve done that briefly, but not on a huge scale, so that’s a bigger goal of mine. I like to see my pieces in movement as well, and it gives me so much joy to see people wearing my pieces out and about. Most of my audience are pretty creative themselves, so I got lucky in that sense.

What other parts of yourself and your craft do you hope to dissect with coming collections?

I have some ideas for the next collection that I really want to explore, although I don’t want to give away too much. I really want to explore beauty pageants because I’m Filipino, and beauty pageants and karaoke are two huge things in the Philippines. I just think showing a more masculine side of a beauty pageant would be really interesting, so I’m thinking of doing that for spring/summer, and everything would be upcycled. I’m exploring, ironically, a more feminine side of myself, but through a masculine lens. Beauty pageants, because they’re so campy, are a really fun way to dissect that for me. So that’s the direction that I’m headed in currently. After spending the last few summers feeling pretty masculine myself, I feel like I’m starting to come into more of a softer, feminine side. But I want to examine that in a way that I’m still poking fun at westernized beauty ideals.