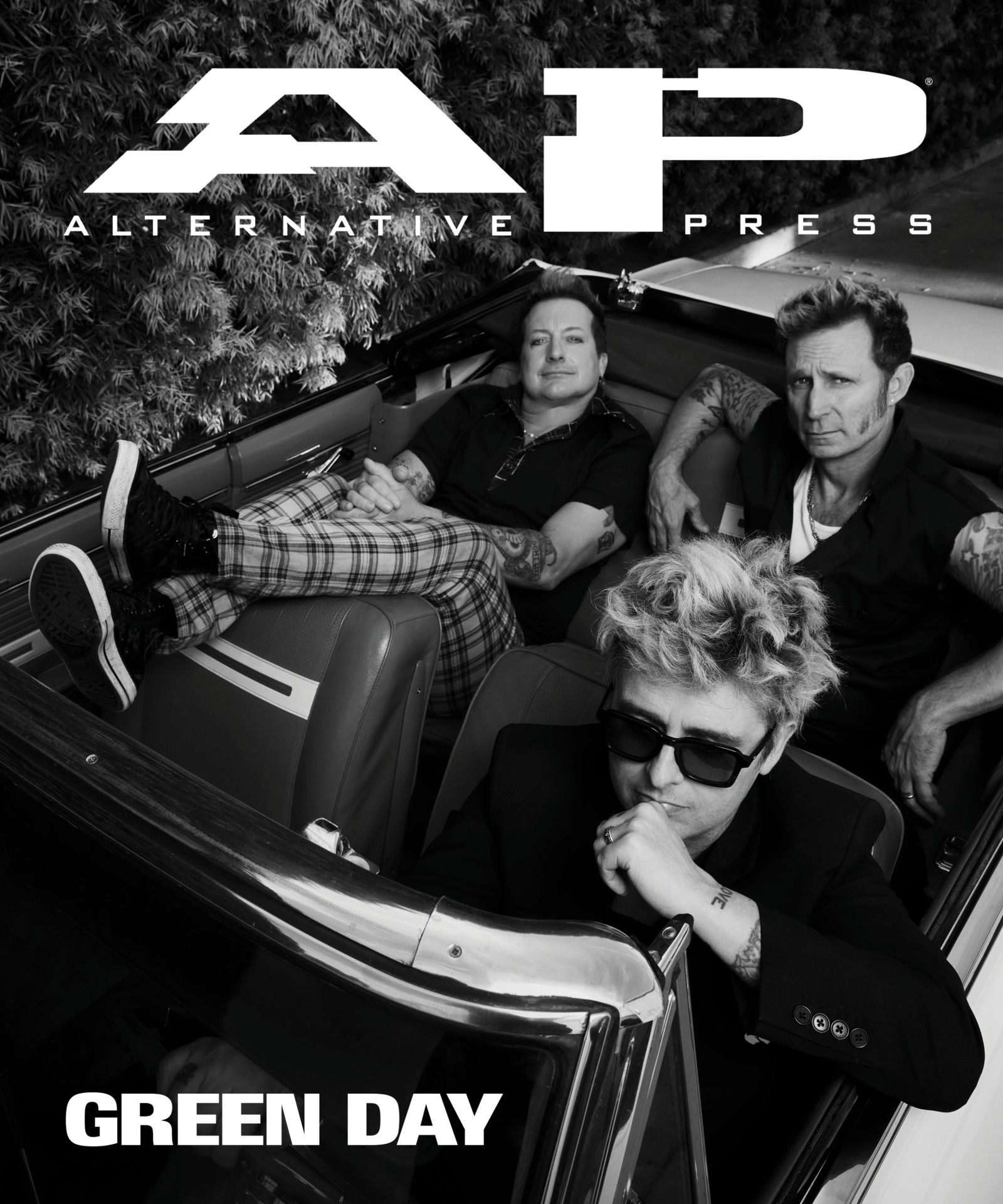

Green Day appear on the cover of the Winter 2023 Issue. Head to the AP Shop to grab a copy and see dates for their 2024 world tour here.

Punk rock is elusive. It’s slippery, avoiding straightforward definition, choosing to reside in the beautiful and fuzzy zone that knows no walls, and retaliates rabidly against any iteration of being “boxed in.” However, the irony of this amorphous scene is that it’s as easy to find solace in its gospel as it is to find oneself slam dancing on a soapbox. Since the genre emerged from the garage-rock scene of the 1960s, the brash sound and subculture we now know as punk has shifted in and out of being an abrasively exclusive club, peppered with judgment, rules, and regulations — an underground community, eager to remain so, in order to maintain its unpolished, anti-establishment prestige.

Charged by angst, the political climate, and pop culture’s sugary and flaccid lack of reaction to the former, punk music pushed back against the commercialized prog rock that had bloated the airwaves and left much to be desired for angered, chaotic youths who were f*cking around, finding out, and fending for themselves. In the U.K., with unemployment at a peak, the Sex Pistols spat and writhed. In the Midwestern U.S., Iggy Pop cut himself with glass in front of an audience. It was more than music — it was shocking, upsetting, and broke many a mold. However, as musical greats throughout history have long since proven, ceilings must be shattered, even within genres that emerged to shatter those same ceilings themselves.

Read more: 10 most criminally underrated Green Day songs

By the time Green Day emerged, a trio of East Bay teenagers fueled by the restlessness and resentment of the American dream in the late 1980s and early ’90s, punk was on the precipice of entering a new epoch, much of which was rooted in California. The void had opened, and a need surged for new voices fueled by angst and honesty, seeing and speaking to the modern world. Fusing sardonic lyricism, heavy rock influences, and a social justice narrative, Green Day filled that void and more. On this exciting wave of punk music, these three were at its crest. Surrounded by snarling, assertive bands like Bad Religion, the Offspring, and Rancid, whether they knew it at the time or not, lead vocalist and guitarist Billie Joe Armstrong, bassist and backing vocalist Mike Dirnt, and drummer Tré Cool were becoming the bedrock that would build a wider, and far more accessible, punk-rock world than ever before, with much more than merely music.

Three decades later, Green Day have a rare opportunity. Each of the members, together yet in spite of the years, sit down and reflect on the past, unraveling two of their most heralded albums, American Idiot and Dookie, as they turn 20 and 30, respectively — and while they ponder the prowess that led them there, and prepare for their 2024 global stadium tour in celebration, they also are looking ahead — opening up in their first conversation about their soon-to-be-released 14th studio album, Saviors (out Jan. 19).

For someone who grew up with the band, the idea of salvation is important here. When Green Day were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2015, Cool gave a sideways grin and said, “Music is the force that gets us up in the morning, and it’s also the shit that keeps us up all night.” Though I don’t play music myself, as a consumer of the art form, I’d like to think this hits home for me in a similar way. I was also an American teenager, discontented and dodging the straight and narrow. I was uncomfortable, angry, and alone. At 12, I met and soon idolized the late Jimmy Webb, who ran Trash and Vaudeville on St. Marks Place, with his slender swagger and stories of the Ramones, begging him to pick out my outfit for the first day of 8th grade. It included an eggplant purple Tripp NYC jacket and a Dookie shirt. In a sea of preppy schoolmates, I stood out like a sore thumb — but I’d never felt more at ease in my own skin. “Punk,” as Armstrong has said, “has always been about doing things your own way. What it represents for me is ultimate freedom and a sense of individuality.” It was after living through 9/11 in New York City that I heard American Idiot for the first time. These rockers were revealing the truth, unveiling the landscape I myself was looking out on, confused and scared.

The energy, and unique outlet, Green Day bestowed upon myself years ago, and their multitudes of fans, has yet to waver. Since my first Dookie tee debuted to little accolade, I continue to turn to the work they’ve made for a solution, self-assurance, company. It’s played in celebration, in moments of fear, lust, or frustration. And with Saviors, the opportunities to escape, rage, and explore continue to be endless. Top to bottom, it plays like a tapestry of Green Day’s triumphant musical moments, full of sonic references that dance from ’50s bops to rough-edged ’70s U.K. grunge. And at the heart of it all? Armstrong remains grounded. As much as ever, he’s looking out, and looking in. “Everything about the record is a reflection of things that I see, or things that I feel, or the way that things make me feel,” he says.

Well, I’ve been listening to the new album. There’s a lot to unpack, and I’m eager to do so with you. From a fan’s perspective, I have to say that Saviors is a gift. This album holds so many eras of Green Day, and so many Easter eggs. It’s like listening to a map, leading through your anthology. There are political references, which feel like an obvious connection to American Idiot, and then there are lyrics that remind me of tracks like “Longview” and “Brain Stew,” with commentary on media and these heavy, dark, physical metaphors. And that’s not to mention the sonic references, which are expansive.

BILLIE JOE ARMSTRONG: With this record, I think it did bridge a gap in our career, as an arc, and all that. But mostly by us being at our best. The way that we went about it was doing what we do best, which is going and starting from scratch, and getting into the studio. Just turn on the amps and let’s go. It was right around the beginning of the pandemic that the first song was written, which was “Saviors.” And then “Goodnight Adeline” and I think “Look Ma, No Brains!” Those songs are the beginning of the map of where you try to unfold what’s going on.

Would you consider Saviors a narrative? Obviously, like American Idiot, when writing a rock opera, it’s more clear cut; it follows characters. But is there a larger story that ties this album together — and why did these tracks feel right for Saviors?

ARMSTRONG: I don’t think we knew it at the time. We were just writing songs, and getting together and playing them. Honestly, there were times where I just wanted to make a straight-up punk-rock record — songs like “1981” and “Look Ma, No Brains!” and “Coma City.” Then there were other times where these lush arrangements started coming out, like “Saviors” and “Father to a Son.” And with “Father to a Son,” obviously it’s about family. It gets deeply personal, almost uncomfortable to even talk about. That song is heavy.

When it comes to “The American Dream Is Killing Me,” that song was actually written about four or five years ago, when we were writing Father of All, but at that time, we didn’t want to go there, to go political. Especially because it was almost like we were expected to. But I played it for Rob Cavallo, and he was like, “Dude, we got to record this song.” And I was like, “All right, let’s go.”

It’s interesting to think about you writing that four or five years ago, and listening to it now, because it feels so deeply hyper-relevant. Which just goes to show the perpetual state of the country — a topic you also talk about on this album, with songs like “Strange Days Are Here to Stay.” I also love that this album truly showcases how impressive your music education is, across genres and eras. What were you specifically pulling from, and what’s your process with the sound?

ARMSTRONG: I pull a lot from melody. That’s what I end up starting with, and then everything unfolds after that. But it’s all different, and things change in the process. “Strange Days” used to be called “I Made a Mess for You,” and then it changed. I did that with “Basket Case,” too. But as far as where I pull from — I listen to punk rock every day. I still love the Who and the Beatles.

It’s impressive how long you’ve maintained the classic lineup, and worked well together, and kept up a certain levity — a sense of humor through it all, even though you’re often talking about truly heavy things.

MIKE DIRNT: This is still our escape, after all these years. It’s an escape for the good and the bad. Sometimes it’s the greatest thing to be in the room. I remember where we were when my dad died. I got the phone call, talked to my brother — we were in New York practicing. I went upstairs, and I’m like, “Let’s just go, keep playing.” I was crying, but we were playing, and it was cathartic. It’s a part of you. It’s an outlet.

Given the depth and weight of Saviors, I can only imagine that feeling of catharsis must have been pretty intense. Before it’s even come out, the internet is pretty gung-ho on some theories — like the album title being 1972. I have to say, the Green Day Reddit threads are certainly alive and well.

TRÉ COOL: That was on purpose.

DIRNT: I like the mystery part of it all. It’s fun, but also, sometimes there’s an idea that we floated, and it fell into something else.

Well, that’s the best part about being a fan. Before this conversation, I spent the last 72 hours trying to understand your album, and I probably went deeper in certain places than you’d all intended, and missed a few wormholes in others. But I guess trying to find meaning is why, and how, music connects us all.

DIRNT: I’m jealous. You got [the] first listen. I’ve never had a first listen of a Green Day record.

It’s special! Especially when it’s another album that you’ve made with Rob Cavallo. How did that come about?

ARMSTRONG: I called him up, just to say hello. And he goes, “You ready to make rock ’n’ roll history again?” I was like, “Oh shit. I was just calling to say hi, but…” Going into the studio with him was great. He’s such a cheerleader, and he’s got so much energy. Sometimes when I get burnt out and I’m tired, I can shut it down a little bit, but still be in the room. And he’ll just say, “Let’s try this. We can do this, we can do this… and oh, my God, I got this old story about working at Warner Brothers.” Then all of a sudden, you’re like, “All right, let’s get back in the room and get a take.”

COOL: One thing I love about working with Rob is he’s able to do the part of making the record that could be harder for us to do, and harder for Billie to do. He can listen and be the critic so that we can just keep trudging forth and making new music, creating it without having to stop, put on the criticism hat, and criticize ourselves. He’s able to do that for us. We’re such great musicians that he rarely criticizes us. [Laughs.] It’s more, like Billie said, a cheerleader.

I mentioned your musical education earlier — this complex range and knowledgeability that I hear in Green Day songs, and I hear even more on this album.

DIRNT: Well, I feel like there’s a lot of performance in this record. Being in the same room, we’re really just playing off each other a lot on this record. You can hear it. It’s really fun.

Is that different from the past?

DIRNT: With this one, there was just more of it. It’s just getting in a room and really getting it. Over time, you go through different ways of writing. Billie will have a song, sometimes fully done. Other times, he’ll want to get in a room and go, “Let’s flesh this out.” And Saviors was a lot more of just getting in, and he’d say, “Look, this is the palette. Let’s just play it. Don’t think about it. Just start playing it together and see what we all pull out together.” I’ve got the headphones in there, and I’m listening. I’m hearing the guitar. I’m feeling Tré’s kick drum, and we’re pushing and pulling off each other.

ARMSTRONG: Also, we were in a bubble, from being on tour together as the first tour out after the world reopened after COVID. So we stayed in that bubble for a couple of years, and it’s almost like, “Well, we’re still in this bubble, so we might as well make it, get into the studio, and continue. If we’re this tightly knit, we might as well keep going.”

As much as I am sick of talking about the pandemic, the level of vulnerability on this, too, feels very introspective, and it makes sense that you had this “bubble” experience. But then you’re also looking out at the societal and political landscape. When I heard American Idiot for the first time, I heard punk musicians really looking out at what was going on in the country and acknowledging that it was desolate. You have that on Saviors, but it also feels like you’re looking inward in tandem. I don’t know if I’ve felt that balance before to this degree on one of your albums.

ARMSTRONG: Anytime I write something that’s topical or political, you have to tackle it coming from the heart, and not just the head. Because for me, it’s more trying to ask, “Why are people in the MAGA movement so angry? What is going on with our country, and the part of it where people are so off that they’re willing to listen to one person, no matter how much bullshit he seems to be spewing?” That, I think, is just trying to have empathy, and maybe that comes from a working-class background, too. I’m just trying to get an understanding of the world. There’s an old saying, “Think before you speak.” People are so knee-jerk reaction to just put their opinion out there about something, and it’s not exactly well thought out. I try to be thoughtful about what I want to say in a song. More like, “Think before you sing,” instead of spouting something you’re going to be stuck with for the rest of your life.

At the same time that you’re working on the release of Saviors, you are also celebrating an anniversary with Dookie. What’s that experience like?

ARMSTRONG: It was so fun to go back and look at all those old demos. It’s crazy because not much has changed in the way that we do things. Back then, we were at this house on Ashby and Ellsworth in Berkeley. Me and Tré lived together, we had a practice space, and we were in there every day. I had a 4-track that we made the demos on.

Pulling out these old cassettes, it was just like, “Oh, my God, this is so cool. I can’t even believe it’s a 4-track.” I was really into British Invasion at that time. I was like, “Man, [songs like ‘Substitute’ and ‘I Can’t Explain’ by the Who] are so timeless. I want to make sure that we can make a record that we feel really proud of 20, 30 years later.” We’re constantly checking in with that, with tones, everything. I could still play “She,” no problem. “Basket Case,” still got the same issues. So I’m really proud about that.

COOL: We’d hear things that were coming out at that time in 1994 and think, “Oh, this is going to sound pretty dated in a few years.” You can just hear it. “OK, don’t do that,” as far as drum tones, guitar tones, and recording qualities.

The level of self-awareness that it must take to make a timeless record, in real time, is so impressive to me. I’m sure that is something you were thinking about consciously in making Saviors, as well.

ARMSTRONG: Yeah, it’s the same tools, except that we recorded on Pro Tools instead of going to tape. But it’s the same characters, in the same movie, so we just went in and did our best.

DIRNT: When writing songs, it helps when you’ve got a song that works around the campfire, as well. You’re not just completely dependent on tones. We’re not just pulling out DX7 keyboards. That has its place, but these songs, it’s all melody.

COOL: We learned at an early age that when the cops come and shut down the party and pull the electric plug, you can still rock the house with good songs, with acoustic guitars.

What do you think are the most fundamental things about each of you that have changed since Dookie came out 30 years ago? As people, as artists, or both?

COOL: We all have many more arrows in our quiver now to draw from. Let me speak in metaphors. When I think about the songs from Kerplunk! and Dookie and Insomniac, those arrangements were very straightforward. And right around with American Idiot and 21st Century Breakdown, we were like, “Let’s break those rules and do something else. Let’s try to do something that is unexpected for the listener who hears ‘Jesus of Suburbia’ for the first time.” We wanted to have that on this record, to be able to throw a curveball musically, in an arrangement — while still sticking with the simplicity of a song.

If you had to sum up what the “purpose” of Green Day is…

ARMSTRONG: Green Day gives me a purpose. That’s one way I look at it. And the purpose is to be the greatest rock ’n’ roll band that ever lived, and with that, I am coming from the most humble place I possibly could come from. But way back, a long time ago, we were always afraid to admit that to ourselves. A couple eras later, we were finally like, “Let’s just be the greatest.”

DIRNT: For me, it’s an individual purpose. To honor this gift and opportunity we’ve been given with our lives, to have found each other — and the ability to do this thing together. I know that the most important thing that I’ll ever leave on this planet is the music that we’re going to create. We all have a similar respect for that, and that creates purpose.

ARMSTRONG: We’ve known each other for so long, and we started making a mess together at such a young age, and it’s just continued and evolved since then. I think that that’s really rare now. You realize, now, how grateful you are that you’re able to have that experience. I mean, I always tell anyone that’s a young band, “Play with your friends. Try to not be a one-man band. Get out of the bedroom and get into the garage with your friends. It’s not going to sound good at first, but eventually, the chemistry will show up.”