Head to the AP Shop for Green Day vinyl, tees, and other merch

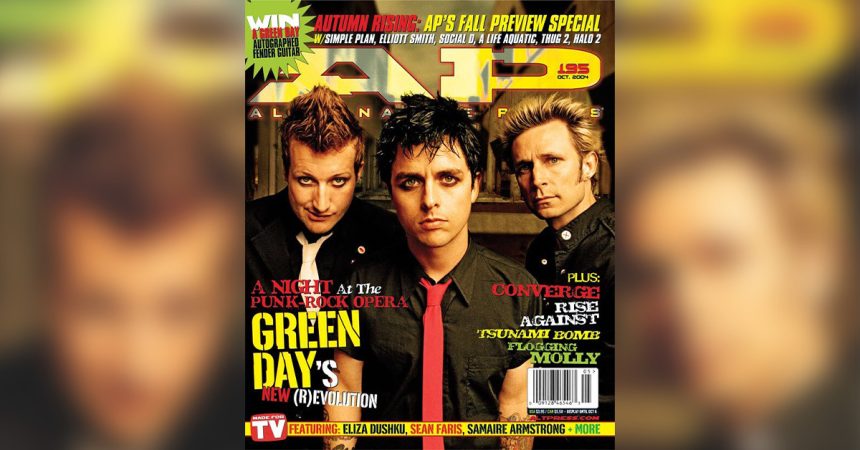

For the cover story of our October 2004 issue (195), AltPress connected with Green Day. The topic of the discussion was the band’s 2004 album, American Idiot. During the interview, band members Billie Joe Armstrong, Tré Cool and Mike Dirnt previewed the new record. Not only did they discuss the themes and political tone of the release, but they also reflected on what it meant for the band to mature and transform their sound on the eve of their groundbreaking album. The content has been modified and adjusted to meet the standards of Alternative Press’ digital platform.

Story: Tom Lanham

Photos: Chapman Baehler

Maybe it’s the aroma of stale pizza and potato chips that hangs in the grease-thick air. Perhaps it’s the lighting system, dimmed to an eye-squinting level that approximates late evening, right before dusk drops into night. Or it could be the piles of empty candy wrappers and drink cans that clog the place, giving it the appearance of some toga-partying frat house. But there’s no mistaking it: There’s definitely an atmosphere of dark oppression that hangs over the dim Hollywood recording studio this particular summer afternoon. And in the center of this murky maelstrom, on a tattered old leather couch, sits a musician who’s feeling suitably oppressed.

Read more: 10 most criminally underrated Green Day songs

Black. Everything is black about 32-year-old Billie Joe Armstrong today. A black pork-pie hat and black leather jacket rest beside him on the sofa. His eyebrows and short, wavy hair are dyed jet black, and his outfit—skinny tie, short-sleeved dress shirt, jeans and tennis shoes—is the inkiest of ebony as well. “But my socks are striped in red and black,” he cracks, pointing to his ankles. His grin quickly fades into set-jawed determination.

The world outside, Armstrong believes, perfectly matches the shadowy mood of this studio. And his multi-platinum punk trio, Green Day, are here for one important reason: to put the finishing touches on an album that mirrors the temper of our turbulent times, a self-dubbed “punk-rock opera” called American Idiot that contains several nine-minute, multi-part epics and is easily the most ambitious undertaking of the group’s 15-year career.

“This is just such a crazy time,” Armstrong murmurs, shaking his head somberly. “And I think our last record [2000’s Warning] was very heartfelt and thought-provoking. But with this one, there’s much more of an instinct thing happening, just running with instinct and going for it. But we live in a really fucked-up time period, and I don’t wanna see my kids…” He pauses, momentarily at a loss for words.

“Well, it’s this culture war, and the country’s divided, split right down the middle, and there’s a lot of confusion,” he continues. “And to be a kid growing up nowadays has gotta be pretty scary because there are a lot of different things pulling you. Whether it’s ‘Wear this fucking deodorant or else you’re gonna smell like shit’ or ‘Watch this reality TV show with this guy putting his head in a big vat of blood!’ And this war that’s going on in Iraq that’s basically to build a pipeline and put up a fucking Walmart. It’s a lot of information, and it’s not only confusing just for my kids; it’s confusing for adults, too.” No matter who you are, no matter where in America you reside or what your political leanings, Armstrong adds, “Everybody just feels like they don’t know where their future is heading right now, ya know?”

A full decade ago, while discussing Green Day’s big-time break from the hip punk indie Lookout! (for which they’d recorded two discs), Armstrong was coiled on another couch, an even rattier one in the basement of the East Bay digs he then shared with Cool and Dirnt. Springs jutted from it at dangerous, ass-poking angles, and duct tape held its stuffing in place. At the time, Armstrong was a scrawny, malnourished kid with a headful of tiny, macaroni-curled tufts of dyed-green hair and a habit of picking his nose, then carefully examining the booger for any abnormalities.

Dookie, of course, would go on to launch a sound, an attitude and a melodic-punk aesthetic that’s being aped almost note-for-note to this day. Thanks to the mainstream popularity of Green Day, the once-underground movement of punk rock was now flourishing on the surface. And like a mole blinking against daylight, it seemed that the only thing it really wanted to do was tunnel underground again.

Since then, Green Day haven’t followed any predictable star-making pattern. Truth be told, they struggled forcefully against fame instead of welcoming it. In 1996, after the self-imposed press blackout surrounding Dookie’s follow-up, 1995’s less popular Insomniac, Armstrong huddled in a Berkeley diner one winter night while three giggling teenage girls ogled him from a nearby booth. Visibly uncomfortable, he dourly noted that he was already thinking of retiring, moving to some desert island with his Dookie dough and never recording again. He was that disgusted with the music business and its attendant pitfalls.

The phase naturally passed. But it was a telling gauge of the young man’s moral compass: He’d rather hang out in his home studio with his wife and son Joey than view all the world’s wonders from the window of a tour bus. Through 1997’s Nimrod (which single-handedly made it OK for punks to croon power ballads via the smash “Good Riddance [Time Of Your Life]”) and Warning, Armstrong’s motives became even more altruistic.

“There was a lot of talking going on with this record,” he continues. “A lot of the growing-up process for us was like, ‘Dude, you’ve been saying the same thing to me since you were 15, and I’ve been hating it for 15 years!’ We just let it all out and declared our places, and then felt comfortable in our places. And it was a very big deal, because now the weird thing is, we feel younger and more revitalized, and we’re having more fun than we ever had.”

Rewind 24 hours earlier, in the spacious lobby of the same recording studio, drummer Cool comes in, decked out in jeans and a flashy green dress shirt, with two 40-ounce green bottles of Mickey’s Malt Liquor tucked under his arm. “A present!” he declares, handing one over and cracking the other open for himself.

“I’m hoping that we’ll be able to make the world a little more sane within the next few months,” he says with a wink. “If the numbers go the right way and we get certain people out of office, that’d be a great start. I mean, Bush is sending over the kids of the people who voted for him and getting them killed. That can’t be good for business. That’s why we think absentee ballots are a great idea ’cause it’s like a take-home test, and you can take your time, vote in your living room.” (The members of Green Day and their entourage will be filing such ballots, he says, since they’ll be performing in Toronto on Election Day.)

Cool adds that he’s pleased with the wild experimentation on the new record. The songs’ shifting time signatures and nearly one-hour duration make it the most strenuous set he’s ever played. But American Idiot had its genesis as a result of two distinct, separate incidents. The first occurred in November 2002, when, from underneath their very noses, the rough-demo master tapes of a full album’s worth of material were stolen. Band members claim they still have no idea what happened to those closely guarded tapes; no ransom note was received, no bootlegs have appeared and no tracks have been file-shared on the internet.

The second momentous occasion? “When Billie wrote the song ‘American Idiot,’” Cool figures, as bassist Dirnt—clad in a muscle-tee and jeans, his dyed-blond hair moussed into spiky quills—shuffles over and pours himself a glass of beer. “Then Mike wrote this 30-second song when we were all out of the studio, then Billie added his own 30-second song after that, and I tacked a 30-second song on, too.”

Dirnt is already chuckling at the recollection. “We each did a 30-second song and tried to make ’em as grandiose as possible,” he says. “And I was like, ‘Damn! That thing sounded huge for 90 seconds! That was really fun!’ Connecting ’em all became this really fun exercise. And once Billie wrote ‘American Idiot,’ he hinted that he really wanted to go in that direction. And we were like, ‘You know what? We can totally fucking do this. It’s within our capabilities.’”

The direction? Dirnt gulps before mouthing the words. “A punk-rock opera. And we were so afraid to say that for a long time. We wouldn’t define it. We were like, ‘Let’s just go in and start doing crazy things.’”

And the earlier, MIA record? “We just let it go,” Cool sighs. “It was like, ‘What are we gonna do? Start all over on it again?’ We were already chasing these new songs, but still we couldn’t help thinking, ‘Fuck, fuck, fuck!’ The weird thing is not knowing where that album is and hoping it doesn’t turn up on our release day, Sept. 21.”

The workout-trim Dirnt is looking scrappy. He’s feeling it, too. Remarried five months ago, he also fears for the future safety of his daughter, especially after seeing Michael Moore’s scathing Fahrenheit 9/11. “It’s a fucking eye-opener,” he says of the film. “And there’s a lot of shady shit going on. The government has thrown so much information at us that we’re all throwing our hands in the air going, ‘I don’t know! I don’t know!’ But I’ll tell you one thing: You don’t have to analyze every bit of information in order to know that something’s not fucking right, and that it’s time to make a change.”

“Punkvoter.com!” Dirnt growls, pounding his fist on the table. “Get the vote on!”

“‘Freedom fries?’” Armstrong can’t stifle a guffaw. “We can’t sit around and blame other countries for the things that we instigate. And we can’t go around telling people that we’re the greatest country in the world because it’s not true. And it’s fine to be patriotic.” Armstrong cites a Scottish audience Green Day recently entertained, which, before the encore, sang their national anthem in unison while the band waited respectfully in the wings. “And that’s a different kind of patriotism, something that comes more from the heart, that sticks up for the underdog. But in America, all this ‘Red, White and Blue’ stuff just becomes…. becomes…. well, just because we’ve got McDonald’s doesn’t make us the greatest country in the world.”

Don’t wanna be an American idiot. Hell, who would? Confusion and punk rock, Green Day will shortly prove, seem to make fine aesthetic bedfellows. And who knows? Armstrong muses. Perhaps some young, visionary filmmaker will transform his work into an actual feature-length flick.

“I feel like I’m on the cusp of something with this,” he believes. “And judging by some of the stuff loaded onto this record, maybe I’m on the cusp of an assassination attempt. But I really feel delirious about this album, like we’re really peaking right now.”

One of the band’s sound techs throws open the studio’s back door, letting in a radiant, almost blinding beam of light before Armstrong politely asks him to leave. The frontman’s Jakob/Joseph tattoos are perfectly illuminated for a minute, and they tug at his conscience.

He frowns. “I haven’t been the most hands-on parent lately, thanks to our recording schedule,” he admits. “And it’s a weird life because I’m easily the youngest father, as far as the people [with children] in my kids’ school or baseball team. And I’m also in that stage where my oldest son is smart enough to know what it is that I do.

“And sometimes he’ll ask me, ‘Dad, are you famous?’ And I’ll go, ‘Well, what does ‘famous’ mean?’ And he says, ‘I dunno, people come up to you at the grocery store and ask for your autograph or say something nice to you.’ And the weird thing is—especially when I’m out walking with him—all of a sudden, some kid with a giant mohawk will come up and go, ‘Fuck yeah! Green Day!’ And Joey will just look at me and go, ‘Who’s that guy?’”

At which point Armstrong can only shrug meekly and confess the truth to his astonished kid. “That was just a guy who really likes your dad’s band,” is what he tells Joey every single time. And once American Idiot shakes the punk-rock world to its foundations, Joey had better be prepared; pop will become even more famous. And the question “Green Day?” will have only one logical response: “Fuck yeah!”