The new entities, nicknamed ‘JuMBOs’, are neither stars nor planets. And they shouldn’t exist, researchers say.

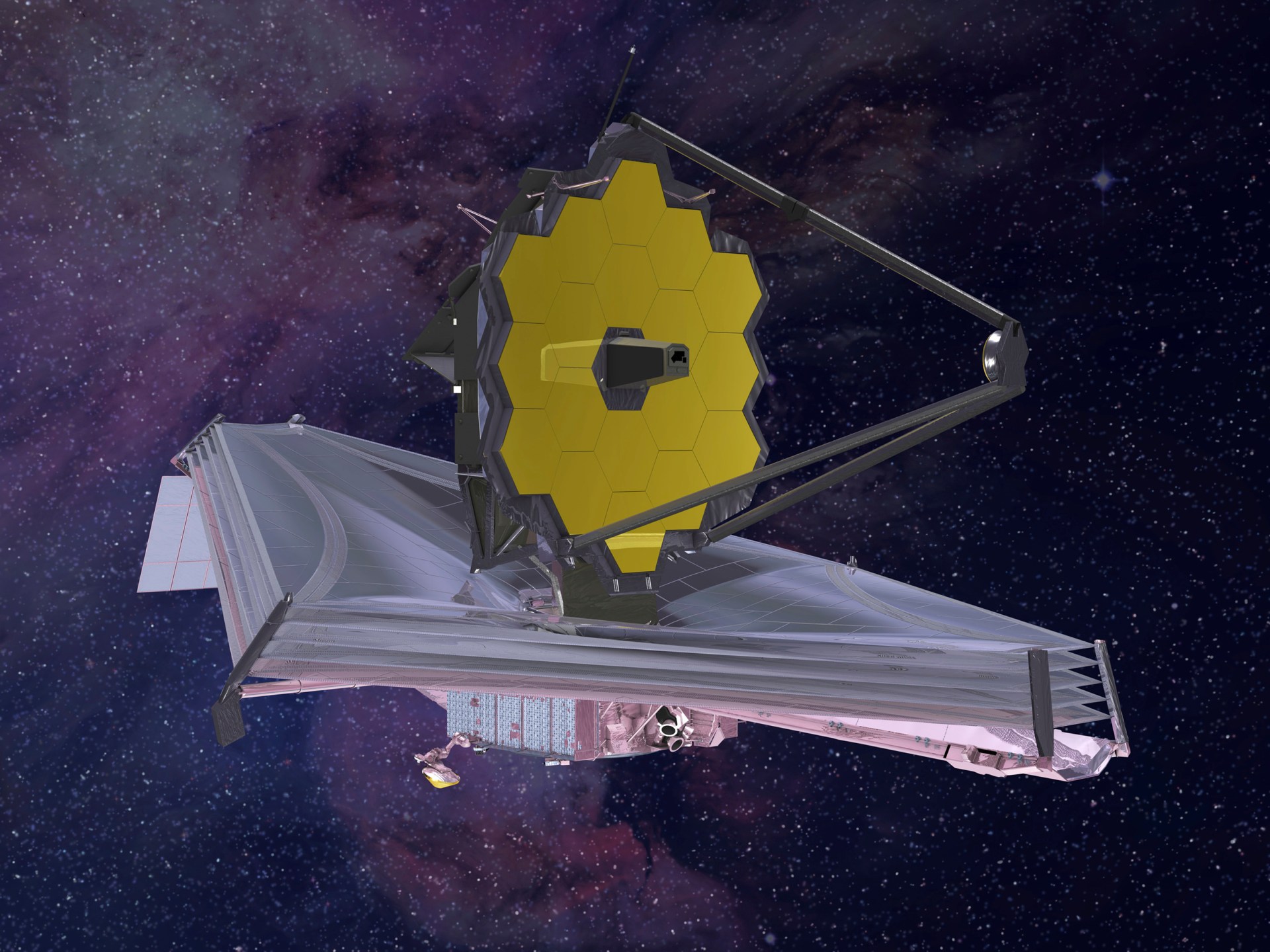

Scientists at the European Space Agency (ESA) have used NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope to make an astonishing discovery: free-floating objects the size of Jupiter, the largest planet in our solar system, in the Orion Nebula, the nearest star-forming region to Earth.

The discovery has upended our understanding of how stars and planets are formed. Before this, scientists thought nebulas, which give birth to stars inside huge clouds of gas and dust, weren’t capable of spontaneously creating planet-sized objects, but the new findings suggest otherwise.

Even more baffling is the fact that the objects are formed in pairs instead of individually.

“There’s something wrong with either our understanding of planet formation, star formation – or both,” Samuel Pearson, an ESA scientist who worked on the research, told The New York Times. “They shouldn’t exist.”

New space images!🤩

The NASA/ESA/CSA James #Webb Space Telescope has added detailed images of the Orion Nebula to our ESASky application.

Zoom into this region with a rich diversity of phenomena including protostars, brown dwarfs and even free-floating planets! pic.twitter.com/In4FQk8hrX

— ESA (@esa) October 2, 2023

The new entities have been called Jupiter Mass Binary Objects, or JuMBOs. They aren’t big enough to be stars, and because they don’t orbit around a star, JuMBOs aren’t technically planets.

“Most of us don’t have time to get wrapped up in this debate about what is a planet and what isn’t a planet,” Professor Mark McCaughrean, a senior adviser for science and exploration at the ESA, told The Guardian. “It’s like my car is a chihuahua-mass pet. But it’s not a chihuahua. It’s a cat.”

According to a research paper that McCaughrean co-authored and hasn’t been peer-reviewed yet, JuMBOs are about a million years old, which makes them young relative to the rest of the universe. Their surface temperatures are roughly 1,000 degrees Celsius (1,800 degrees Fahrenheit).

But unlike planets, which are eventually able to maintain consistent temperatures thanks to the energy they receive from the stars they orbit, JuMBOs eventually cool down rapidly and freeze. They’re also largely made up of gas, which means they’re unlikely to be able to support life.

Scientists have multiple hypotheses for how JuMBOs came into being. The first is that they were formed in areas of the nebula too sparse to create proper stars. The second is that they were formed as planets meant to orbit stars but then got “kicked out” for unknown reasons.

“The ejection hypothesis is the favored one at the moment,” McCaughrean told the BBC. “We know single planets can get kicked out from star systems. But how do you kick out pairs of these things together? Right now, we don’t have an answer. It’s one for the theoreticians.”

Other scientists called the pairs phenomenon unprecedented.

“My reactions ranged from ‘Whaaat?!?’ to ‘Are you sure?’ to ‘That’s just so weird’ to ‘How could binaries be ejected together?’” astronomer Heidi Hammel, who was not on the research team, told the BBC.

No current scientific models, she said, predicted pairs of planet-sized objects being ejected from a nebula but added that maybe there just hasn’t been a telescope powerful enough to spot them before.

Scientists and astronomers have studied the Orion Nebula for years to observe the formation and early evolution of stars and other celestial objects.

It lies 1,350 light years away from Earth and is visible to the naked eye as a misty smudge at the bottom of the Orion constellation, part of the “sword” of a mythical Greek hunter whom the constellation is named after.