Three years after hundreds of people were killed in the port blast that devastated Beirut, religious leaders and rights groups decried the lack of accountability among political leaders who stymied the official investigation.

Friday marks the anniversary of the enormous blast on August 4, 2020 which destroyed swathes of the Lebanese capital, killing more than 220 people and injuring at least 6,500 others.

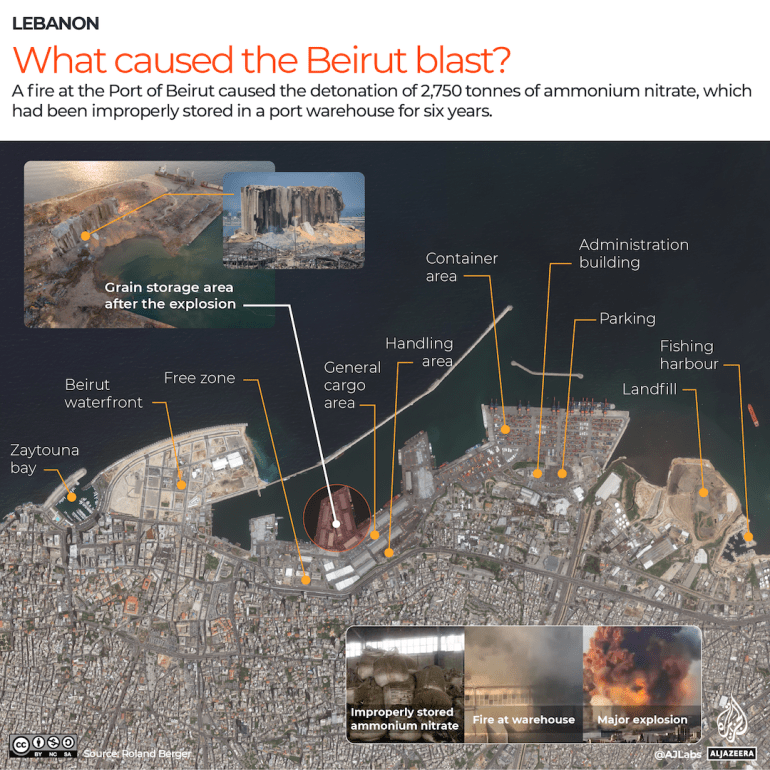

Authorities at the time said the disaster was triggered by a fire in a warehouse where a vast stockpile of industrial chemical ammonium nitrate had been haphazardly stored for years.

Three years on, the probe is virtually at a standstill, leaving survivors still yearning for answers.

Lebanese and international organizations, survivors and families of victims on Thursday sent an appeal to the United Nations Human Rights Council, saying that “on the third anniversary of the explosion, we are no closer to justice and accountability for the catastrophe”.

Maan, a Lebanese group advocating for victims and survivors, put the death toll at 236, significantly higher than the government’s count of 191. The authorities stopped counting the dead a month after the blast, even as some of the severely wounded died in the subsequent period.

Lebanon is home to more than one million Syrian refugees, who make up about 20 percent of the country’s population. A Lebanese group, the Anti-Racism Movement, said that among those killed in the blast were at least 76 non-Lebanese citizens, including 52 Syrians.

Maan, the main activist group representing families of those killed, has called for a protest march on Friday afternoon, converging on the port.

“This is a day of commemoration, mourning and protest against the Lebanese state that politicises our cause and interferes in the judiciary,” said Rima al-Zahed, whose brother was killed in the explosion.

“The judiciary is shackled, justice is out of reach, and the truth is shrouded,” she told the AFP news agency.

Slow investigation

The blast happened amid an economic collapse that the World Bank has dubbed one of the worst in the country’s recent history and which is widely blamed on a governing elite accused of corruption and mismanagement.

Since the days following the explosion, the probe into the blast has faced a slew of political and legal challenges. In December 2020, lead investigator Fadi Sawan charged former prime minister Hassan Diab and three ex-ministers with negligence. But as political pressure mounted, Sawan was removed from the case.

His successor, Tarek Bitar, unsuccessfully asked lawmakers to lift parliamentary immunity for members who were formerly ministers.

The powerful Iran-backed Hezbollah group has launched a campaign against Bitar, accusing him of bias and demanding his dismissal.

The interior ministry has refused to execute arrest warrants that the lead investigator for the disaster has issued.

In December 2021, Bitar suspended his probe after a barrage of lawsuits, mainly from politicians he had summoned on charges of negligence.

But in a surprise move this January, Bitar resumed investigations after a 13-month hiatus, charging eight new suspects including high-level security officials and Lebanon’s top prosecutor, Ghassan Oueidat.

Oueidat then charged Bitar with insubordination and “usurping power”, and ordered the release of all those arrested over the blast.

Bitar has refused to step aside, yet he has not set foot inside Beirut’s justice palace for months.

“Work [on the investigation] is ongoing,” said a legal expert with knowledge of the case, requesting anonymity due to the sensitivity of the matter.

Bitar is determined to keep his promise to deliver justice for the families of the victims, the expert added.

Justice delayed

Many in Lebanon have been losing faith in the domestic investigation and some have started filing cases abroad against companies suspected of bringing in the ammonium nitrate.

The chemicals had been shipped to Lebanon in 2013. Senior political and security officials knew of their presence and potential danger but did nothing.

Lebanese and non-Lebanese victims alike have seen justice delayed, with the investigation stalled since December 2021. Lebanon’s powerful and widely-considered corrupt political class has repeatedly intervened in the work of the judiciary.

On Thursday, 300 individuals and organisations including Human Rights Watch (HRW) and Amnesty International renewed a call for the United Nations to establish a fact-finding mission, a demand local officials have repeatedly rejected.

Aya Majzoub, Amnesty International’s deputy regional director for the Middle East and North Africa, accused authorities of using “every tool at their disposal to shamelessly undermine and obstruct the domestic investigation to shield themselves from accountability”.

In a memorial church service on the eve of the blast anniversary, Lebanon’s top Christian cleric Patriarch Bechara Boutros al-Rai backed calls for an international fact-finding committee and called for a halt to meddling in the blast probe.

“What hurts these families and hurts us the most is the indifference of state officials who are preoccupied with their interests and cheap calculations,” al-Rai said.