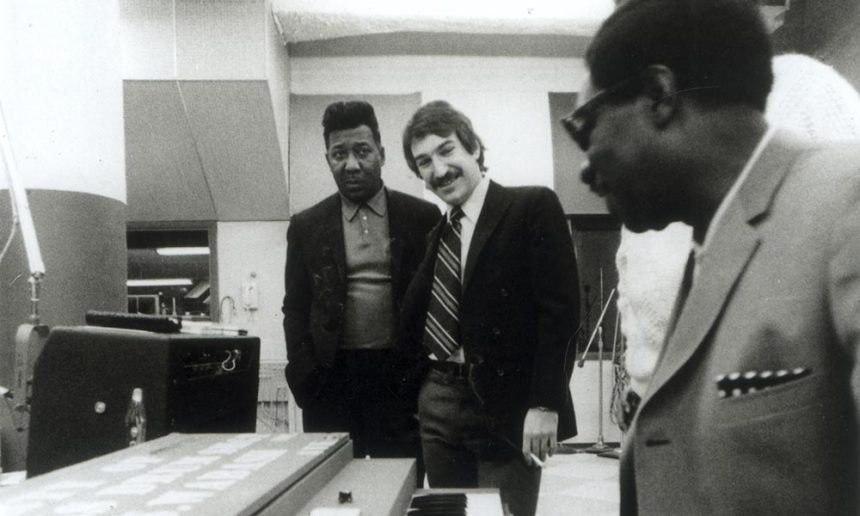

Marshall Chess has spent most of the time since leaving the Stones in the late 70s working with the hip-hop label Sugar Hill Records. He and experimental drummer Keith LeBlanc have collaborated on New Moves, a new release that melds two disparate styles, hip-hop and blues, into a sound that appeals to a wider audience than either does independently. In other words, New Moves promises to do what Marshall did in the late ’60s when he put Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf together with progressive rockers to create a sound that appealed to both electric Chicago blues fans and a younger, mostly white crowd that loved what Marshall had done as the Stones’ producer on several of their albums.

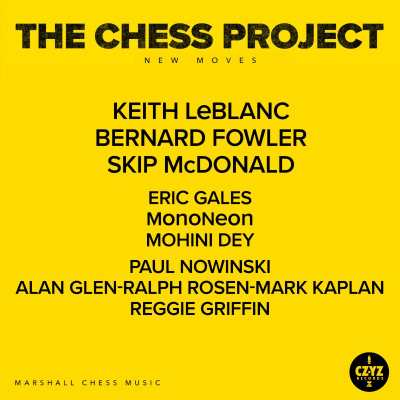

LeBlanc plays drums on the album that contains songs written by Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and Sonny Boy Williamson. Skip “Little Axe” McDonald is on guitar and longtime Rolling Stones backup singer Bernard Fowler is the vocalist. The album is on CZYZ Records. CZYZ is the Chess family’s original name in Poland before Leonard and his brother, Phil, immigrated to Chicago and Americanized the name to Chess and founded Chess Records in 1950. It became the most successful electric blues label.

The question is will lightning strike again? Will this new sound once again find favor with a young demographic brought up on the sounds of hip-hop? Does 1 & 1 = 2? Will the hip-hop crowd embrace the blues the way the alternative rock fans embraced real deal blues in 1969?

Marshall explained things this way to me back in 2000: “One of the reasons that gave the early electric blues such magic was the alchemy that was created by two-track recording where there weren’t any overdubs. There weren’t chances to correct mistakes. The way I learned to produce was to keep the session rolling and get the band to lock together because if one guy kept making a mistake, you had to keep recording. You couldn’t fix the bass later. You couldn’t put the vocals on next week. The way they make records today, it’s in pieces… I wanted to see if I could get some of that early magic by making them all lock together.”

“Marshall would send me a bunch of the tunes,” says Keith LeBlanc, “and I would look through them and see which ones I had ideas for, and he’d come back (with classic Chess blues cuts) going back to tunes like that. I’d just come back from England, and I didn’t know anybody in the states anymore. The last thing I did was a Nine Inch Nails album, and then I moved to England. I didn’t even know it was a smash hit until I moved back, and I called Marshall and said, ‘Do you have anything interesting?’”

“I kept expanding it,” says Marshall, “but that’s what inspired me, and I tried to inspire Keith with this record. The only thing that is basic blues on this one are the lyrics, you know? We took it to another market, hip-hop/funk. He can describe these grooves. He made ’em, but they weren’t straight blues, you know? Yeah, they hated me (for Electric Mud). I think the blues purists will probably hate this album, too. But a lot of people are loving it.

“There are songs that have lyrics that I played when I had problems with women. My first wife cheated on me. These were men’s songs. ‘Going Down Slow’ and ‘Mother Earth’ ’cause I’m 81, man. They’re great songs about getting ready to die, you know. I chose these songs, and they all mean something to me in a psychological way.

Marshall sent Keith some of the classic cuts to be considered. “I was just throwing stuff against the wall to see what works,” continues Keith. “They’re all 2-tracks. I ended up chopping out all the vocals and making two tracks from them, and I basically took a hip-hop vibe on it ’cause I’d done a lot of that. I didn’t know anything about the blues, so I didn’t have any prejudices about it.

“And I was lucky because the more out there I went with it, the better Marshall liked it. He’s not a regular record guy, you know? He’s more like a member of the band. So, I never looked at him as your regular record person. It’s a combination of funk, jazz guitar, reggae stuff.

“It’s all in there and trying to stick with the instrumentation of the blues for the most part. I was just really trying to get something that I liked and that Marshall liked. That’s what we focused in on. We didn’t really focus in on ‘Oh, this really has to be a blues record,’ because the lyrics are very bluesy. You can recognize the song from that.

“I was playing with one of the first bands doing hip-hop in the early ’80s. Hip-hop was fun. It actually was a lot of fun, and it’s changed over the years and got pretty dark. So, it just turned into something that really moved us.”

It was that alchemy that Marshall discovered working with The Stones. “When I did my first record with them, which was Sticky Fingers, the one with the zipper on it. Man, I couldn’t believe it because what would happen was they would come into the studio. They hadn’t seen each other in five months, and the engineer in the control room was Glyn Johns, a famous English engineer at Olympia Studios in London. They’d start playing, and he’d be fiddling with the mics and come back the next night, and they’d be jamming around. All of a sudden, the third or fourth night, it was like the alchemy – the magic.

“They would lock together and boom, they would cut five tracks in a row. And they’d write the lyrics later, or they’d have scratch lyrics. Remember ‘Tumbling Dice’? That was called ‘Good Time Woman.’ That was one of them. They would just rewrite the words, come back, and we’d do that. But the band usually went down the same way all at once. That same kind of thing. Yeah, they’re my favorite. Look, I loved all that. I love The Kinks. I love Eric Clapton. I love the Yardbirds. I loved all that early English stuff.”

Leonard Chess encouraged his son Marshall to find new markets for the blues in the ’60s. “My father said to me, ‘See what you can do to spread our shit in this new market.’ I did what the blues people loved at first. I did The Real Folk Blues series. More Real Folk Blues, The Super Blues Band, Two Great Guitars. They were classic albums, with the classic old cuts.

“I researched the stuff, and then I smoked a lot of pot. That whole generation hit, and I was part of it. I became one of them, and it started that whole alternative radio thing across America, FM alternative radio where they would play anything. I was one of them. I was a psychedelic guy, and I said I wanted to start my own label. I had ideas for this new market, and my father always said, ‘Don’t be too far ahead of yourself. That’s the same thing as being too far behind, you know?’

“He’d tell me that. He took the same kind of shots with the blues, with echo, with all kinds of things. So, that’s what happened, man. So, I found in Chicago what I felt – it’s like what we have on this album. The best guys I could find – Phil Upchurch, Lewis Sesenfield on bass. These are brilliant top players in Chicago and I had Charles Stephanie, a great arranger. I did this album Rotary Connection that was a psychedelic hit. It was our first album and sold like 150,000.”

The Transition of black blues for an increasingly white audience was controversial. “As I explained to these cockroach purists, I didn’t want Muddy to change. There’s nothing like the original blues to me. I still get chills when I hear it; but I wanted to get these new people, white pot smokers, bring ’em in – which was my idea. I talked to Muddy about it. I said, ‘Will you trust me? There’s a whole new thing happening. You know it yourself, Muddy. Look at the gigs you’re playing. More and more of the hippies coming to hear ya.’”

“Yeah!”

“‘You know it yourself. There’s a new day.’ And he trusted me because of my father. He trusted me just like he would my father. He gave me full trust. If he didn’t like it after it came out, would he have done After the Rain, the second one?”

Will lightning strike again for Marshall Chess? Will New Moves expand the blues audience? Will it inspire a new creative direction in the genre? Will hip-hop artists and fans take a new look at the traditions that have made American music the envy of music makers around the world? Will revamped songs like Howlin’ Wolf’s “Moanin’ at Midnight” and “Smokestack Lightning,” Sonny Boy Williamson’s “Nine Below Zero” and “So Glad I’m Living,” and Memphis Slim’s “Mother Earth” awaken a renewed zeal for the music that is bedrock of the American songbook?

Only time will tell.

Read part one of our Marshall Chess interview here and part two here.