Zulu appear in our Winter 2023 Issue with cover stars Green Day, 070 Shake, Militarie Gun, and Arlo Parks. Head to the AP Shop to grab a copy.

Anaiah Rasheed Sayyid Hadi Muhammad has been playing drums in punk bands since he was 12. Now, for the first time, Muhammad finds himself at the front of the stage with an audience eager to listen to him.

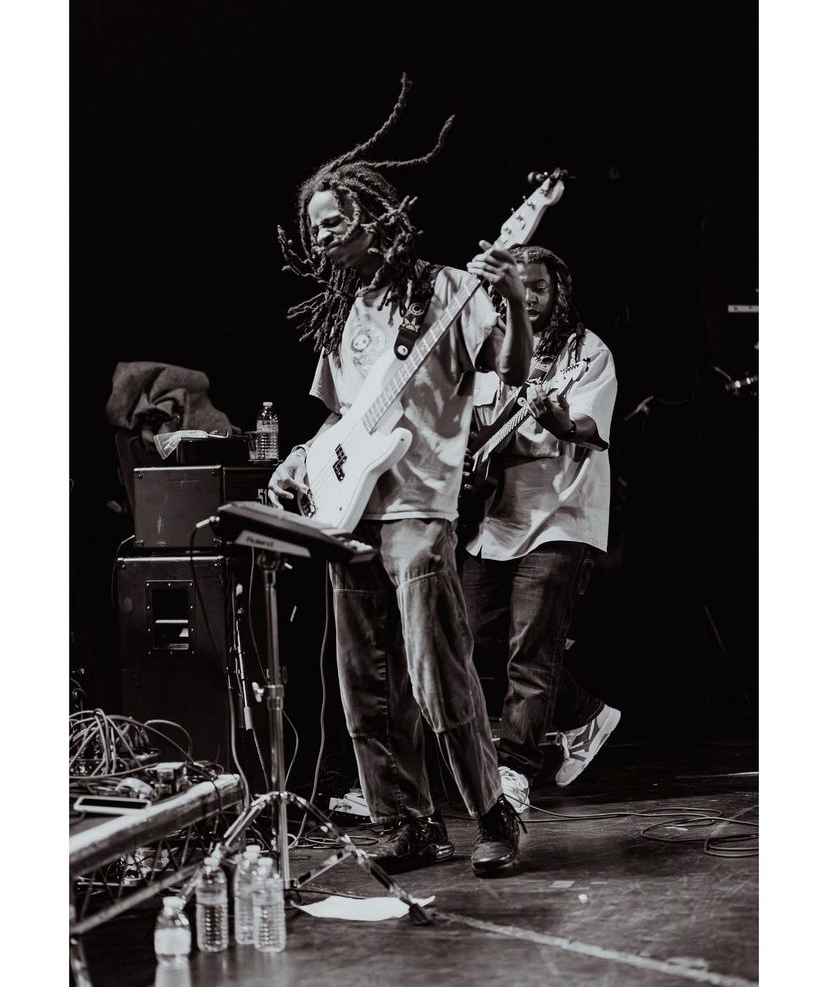

In just a few short years, Zulu, the Los Angeles-based hardcore band of which Muhammad is the frontman and primary songwriter, have released two EPs and their debut record, A New Tomorrow, played festivals with LCD Soundsystem and KAYTRANADA, released a music video with comedic genius Eric André, and amassed nearly 95,000 monthly listeners on Spotify alone.

Read more: 15 best modern hardcore bands for day one fans

Central to Zulu’s identity, and the reason so many people care deeply for the band, is an unabashed celebration of their roots and experiences as Black folks in America. The band have made a point to champion Black voices while expanding the look and feel of hardcore, incorporating carefully curated samples of classic soul, reggae, and dub within their fast and driving powerviolence riffs.

Muhammad is getting comfortable in his new role at the forefront of a punk band, but with that, the vocalist is also grappling with the challenges that come along with gaining success as an outspoken group that don’t adhere to the subculture’s unwritten rules.

Since hardcore’s inception in the 1970s, it has been a rather insular community that operates on the fringe of the mainstream — in basements and back alleys, in rundown venues, and led by people who adhere to their own moral code. Hardcore, for decades, has lived and thrived through word of mouth and has been largely ignored by record labels, music journalists, and industries that have the means to make music a profitable endeavor. As a result, the subculture carries with it a deep-seated history of gatekeeping and exclusivity. The outcome, for better or worse, is that a debate about whether or not a band are “a hardcore band” is as much about image and ethos as it is music.

So when a band like Zulu suddenly explode not only onto the scene but also garner mainstream recognition, those who have a very specific idea of what a “hardcore band” look and sound like become weary.

Muhammad is aware of the discourse that surrounds his band, but no longer entertains it, saying, “If people can’t accept us in the general scene, we’ll just do our own thing. We’ll create our own space within it.” Instead, he remains focused on cultivating a positive environment for himself and expanding what “hardcore” can mean. Looking at the success of their first headlining tour, it’s clear that Zulu’s dedication to cultivating an inclusive community has been paying off.

Tell me about the tour that just ended. How was it?

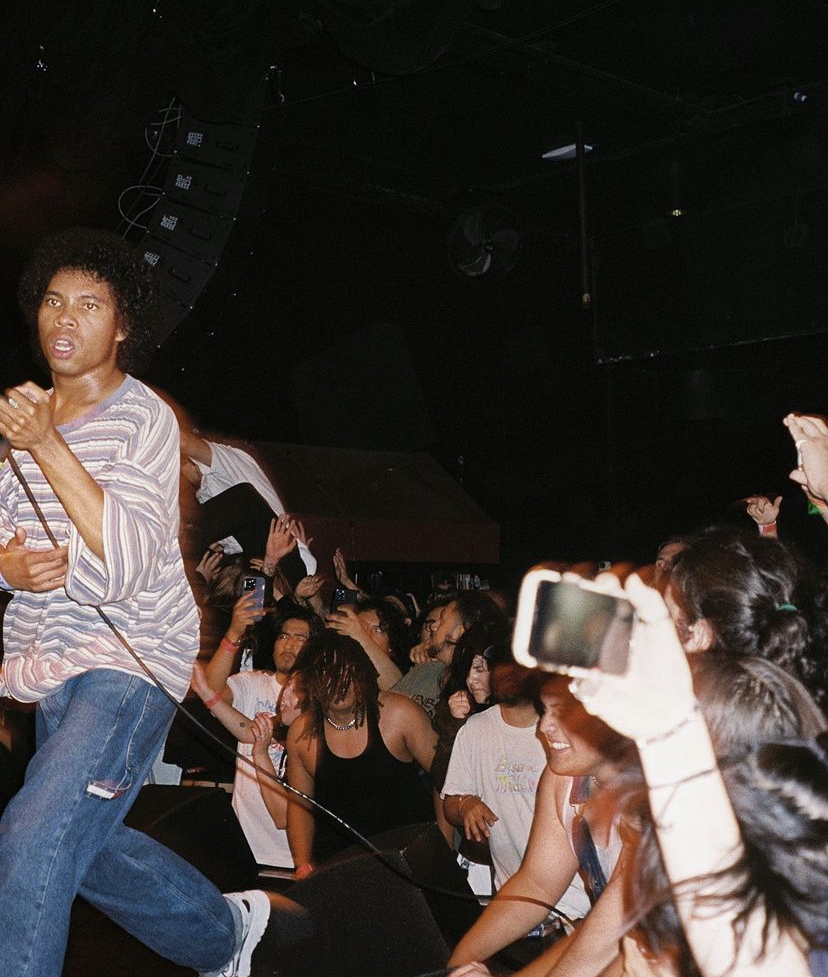

It was our first headliner, and it went over really well. I didn’t know what to expect, and it actually exceeded all the expectations that I had. I didn’t realize how many people really liked us.

I see Zulu shirts all over the place nowadays.

It’s interesting. You know, I’ve played in a million bands, but this band has been something different.

There are people who really look up to you. As a band that promote the messages that Zulu do, it can lead to people viewing you as a role model of some sort.

It’s cool. It sometimes feels like a lot of pressure, but I’m flattered. It’s an honor when people say stuff. It means a lot.

Because of Zulu’s popularity, you are the entrance that a lot of people have to hardcore or even heavy music in general. Knowing that, what do you tell people?

A lot of people seem to think we’re the first band to say some of the things we say and play this style of music, but there’s an extensive history of bands that have sounded like us and talked about the things we talk about. I try to just tell them, “Hey, check this out. Listen to this. These are the bands that inspired me” if you’re interested and want to hear something that is similar to us.

I’ve noticed that a lot of the conversation surrounding Zulu treats you as a statement about an entire community, rather than allowing your lyrics to be personal. I wonder if you ever feel tokenized or like a poster child for a certain movement.

All the time. I feel the exact thing that I didn’t want to happen happens all the time. The last thing we want is to be tokenized. I want people to know that I’m not speaking for everyone — I can’t speak for everyone. I’m not a monolith. I do talk about personal stuff in my lyrics. Maybe people just equate it to a generalized statement about an entire community when actually I’m just talking about the things I’m going through. If you take time to stop tokenizing and look deeper into us, you’ll see Zulu is more than just a political statement or a mission statement.

Hardcore bands are normally given the space to talk about a variety of political, humanitarian, and personal beliefs and experiences, but it seems to me that sometimes POC-fronted bands are reduced to one message. Is that what you mean?

At some point, I wonder if we’re even talking about my band. Are we talking about our music? Or are we just talking about the fact that we look the way we do? It’s obvious what the issue is and that there is still work to do. If people can’t accept us in the general scene, we’ll just do our own thing. We’ll create our own space within it.

It seemed like your tour with Soul Glo and Playytime was very successful in that regard. How do you stay sane and grounded when touring extensively?

When I’m home, I just do the most mundane things. I don’t do a lot. I feel like from touring so much, I get all of the social time that I need, so it helps to have that balance of life when I’m back. It just helps to be on the more chill side. I like touring, don’t get me wrong, but at a certain point, I really do like being back in LA. I noticed that I like to tour with this band more than any other band because of the spaces that I am in when I’m in this band, as opposed to some of the more judgmental spaces I’ve played in with other bands.

Any crazy moments from this past tour?

Every day it was a positive moment. We played a hometown show at The Roxy. You know, every time you play a hometown show, you have all your friends come out. It was amazing.

When you think of a successful show, what does that look like? What makes a show special?

It doesn’t matter to me how many people are there. What makes a good show is when you can tell that people had a good time as well. It’s so cheesy to say, but if we’re all having fun, the vibe is good the entire time, the people in the crowd are having a good time, then we’re all having a good time together.

I don’t think that is corny at all. As someone who has had pretty extensive experience not just touring, but also working in the music industry, what is it that keeps you coming back to hardcore and heavy music? When there are so many things you could critique about the scene, what keeps you excited?

That’s a good question. Sometimes I even ask myself that. I could do anything else. Why keep coming back to hardcore? The answer is, there’s just nothing like it. There is really nothing like it. You can’t even explain it to people.

I see a lot of people who got started playing in punk or hardcore bands get successful and move out of the space onto more profitable endeavors, so to see someone like you, who is still excited about heavy music, it’s inspiring.

I love writing [heavy music]. I want to do other stuff while also maintaining my identity by blending other genres within our set. We did it on this last tour, and in that setting, it works. If people don’t get it or think it is cheesy, I don’t care. I am incorporating all of the things that interest me.

You’ve always been into a variety of music genres. I know that dancehall and reggae have always been a part of your life.

Absolutely, 100%. If I could go out and dance all the time, I would. It’s very much a cultural thing. It’s pure.

You incorporate a lot of samples into Zulu’s first full-length, A New Tomorrow. Are you happy to have it out in the world? Are you happy with the reaction that it’s gotten?

This being the first LP, I was nervous about how it was going to be received. I would hope people like it, but it exceeded what I expected. It’s wild to see the spaces it’s reached, you know? It’s insane to see the people that have been introduced to hardcore through our record.

There is a lot of hope, love, and positivity within the record, but I read in another interview that you made some personal life changes that made it easier to focus on putting positive energy into the lyrics. What are those changes, and how did it affect the writing?

Getting really personal. At the time [of writing], I was shifting out of bands that I played in and was putting more focus into Zulu. Old friends were leaving my life, and I was going through relationship stuff. I was changing as a person drastically. By the time we were first writing the record, I was in a really crazy, terrible place mentally, so the record was really bleak. At some point, I was just like, “This doesn’t feel right.” I’m glad that version didn’t come out because it wouldn’t have been anything close to what this record is now.

It wasn’t the type of message you wanted to put into the world?

It was really just mad. It was sad, negative energy. I was getting over all of that stuff and trying to come into the person I wanted to be because for so long, I wasn’t myself.

Do you think that writing a record like this helped you get out of a funk and push yourself into a more hopeful, positive mindset?

Believe it or not, it did. I’m glad I had time to sit with what I was feeling. Sometimes you write what you’re going through, and that’s fine, but at the same time, you’re going to change and you’re going to shift, so it’s about how you will feel after it comes out. Halfway through writing the record, stuff got better. I was working really, really hard to get to where I felt like stuff was going to be OK because it felt like it wasn’t OK for so long. By the time I felt good, I had a whole different outlook on life, so I said, “All right, I’m scrapping these lyrics because I don’t want to just write grim stuff all the time.” My life, the whole band’s life, is way more than just negativity.

You’ve been in the back drumming your entire career until now. Are you getting something different out of music now that you’re in a band as the frontman?

It’s very, very different. The attention you get with it is interesting. I don’t think I’ve ever been an attention-seeking person very much, and that just comes with fronting a band. For a while, it was nerve-wracking trying to talk about anything when stepping into the role of being the frontman. You’re the person that people look to. I felt like, “Oh, maybe I have to have a persona or act a certain way,” which has never been me. So now, I just try to be authentic no matter what the situation is, but it can be overwhelming, I’ll be real.

What are you looking forward to doing with Zulu?

We’re just planning our year and chilling for a second. That’s it.