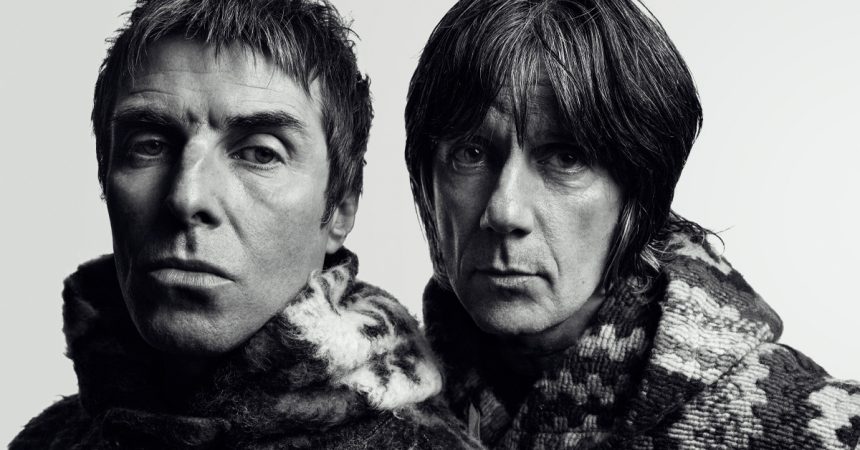

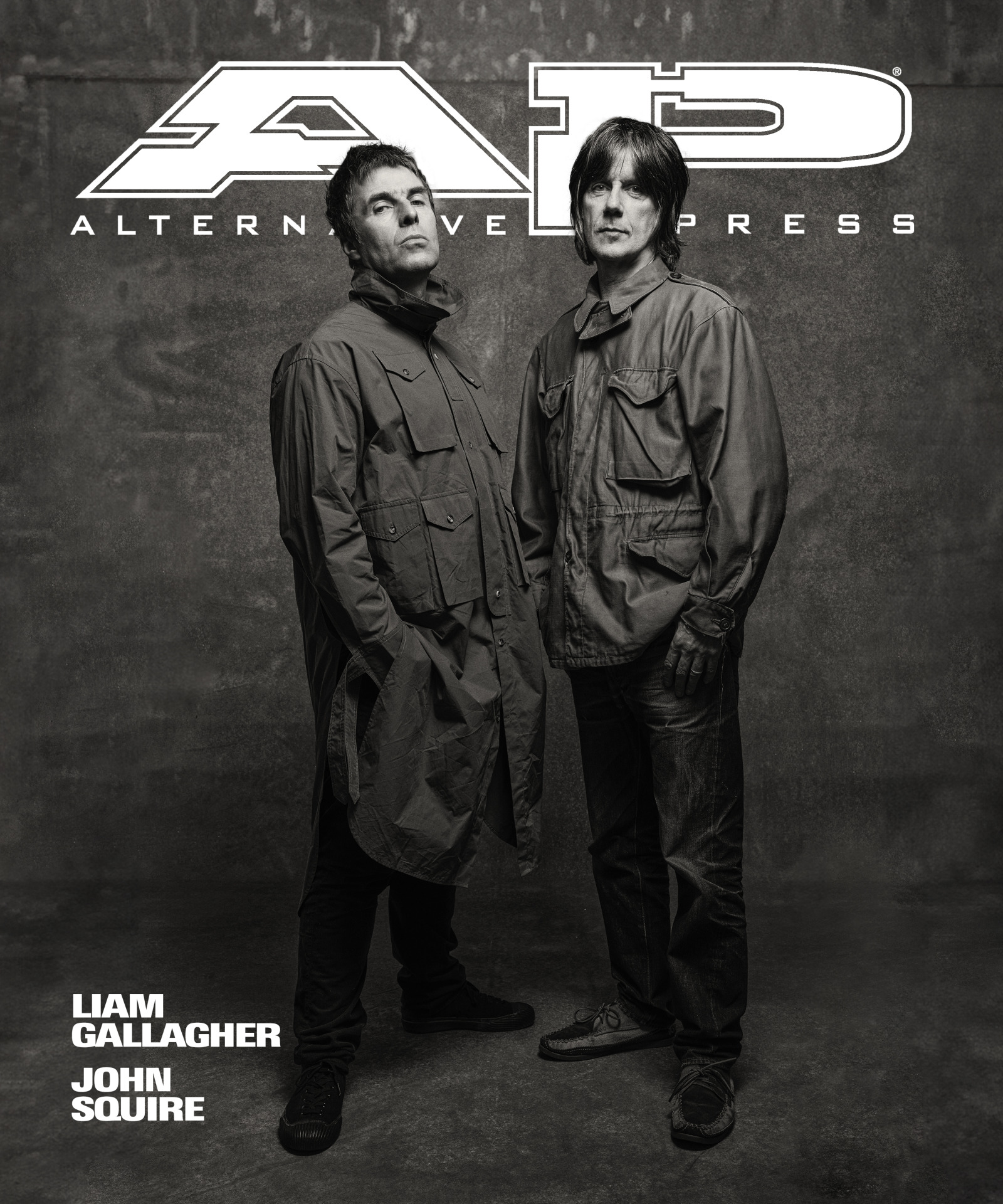

Liam Gallagher and John Squire appear on the cover of the Spring 2024 Issue — head to the AP Shop to grab a copy.

It’s March 1, 2024, and Liam Gallagher is on X, with William Shakespeare on the mind. “Be not afraid of greatness some are born great some achieve greatness and others have greatness THRUST upon them,” his latest post reads. Though Gallagher has a proclivity toward out-of-context posts, or so they seem, this one — cheek notwithstanding — is actually apropos. Today, Gallagher, alongside fellow Mancunian and modern-rock figurehead John Squire, have released an album. And this moment, whether by an intrinsic compulsion to create or simply the call of rock ’n’ roll, can certainly be considered one “THRUST” upon them — not unlike the humble journey that took Oasis to ring in the millennium with record-breaking fame, or the Stone Roses to release one of the greatest British albums ever recorded.

Among other adjectives — spiritual and biblical being a few — Gallagher, also on X, deems the album, which has been given the matter-of-fact title Liam Gallagher John Squire, “crucial.” Allowing room for the subjectivity and context of such a claim, the crucialness holds weight, which I concede after spending time with the album, speaking one-on-one with both Gallagher and Squire, and then chugging espresso while burrowing into the deepest recesses of the internet, lost in a British rock history wormhole. While I come up for air feeling “fucking pickled,” to use a term Gallagher threw out during our Zoom call, and like less of a musical cartographer than a paranoid detective with a board of strings and pins, fumbling from the Beatles to the Byrds to Bo Diddley — this exact desperate desire to dive in, find meaning, recontextualize and relate is a crucial, transportive experience for an audience.

Read more: 15 greatest supergroups across rock, punk, and metal

It was an equally momentous, and sacred, act for the artists to make Liam Gallagher John Squire. Prior, Squire’s future in the art form was uncertain. He’d taken a break from music, favoring his other medium of choice, fine art and painting, following the Stone Roses’ reunion of 2011 and 2017 disbanding. However, the choice became less autonomous and more circumstantial during the pandemic when Squire, in breaking a fall, broke the scaphoid bone in his hand, an injury without a guaranteed full recovery, and arguably an artist’s worst nightmare. “It was a wait and see whether you’d get full use of it back kind of thing,” the soft-spoken musician tells me. “So when that sunk in, and I realized that it would affect both making art and making music, I was scared shitless… When it came to rehabilitation, I really went for it with the physio, and started getting guitar strength back as well.” The recuperation period saw Squire playing guitar intensively, with newfound dedication. It was at this point that Gallagher’s team reached out about Knebworth.

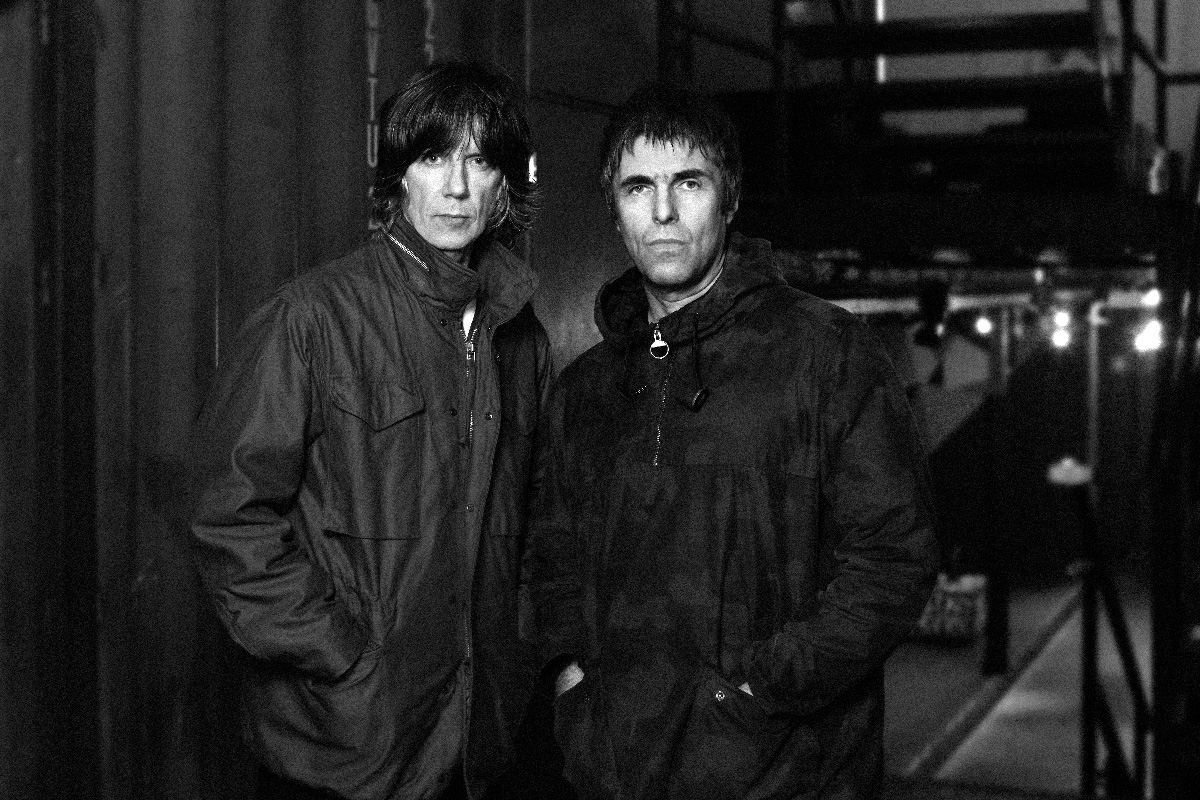

![Copy-of-G_S_Press_0862-RGB-[credit_-Tom-Oxley]](https://www.altpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/12/Copy-of-G_S_Press_0862-RGB-credit_-Tom-Oxley.jpg)

To unravel the threads that connect it all together, from Squire to Gallagher, Oasis to Stone Roses, the guitar to the piano to the vocals on Liam Gallagher John Squire, context is key. And so is Manchester. Before the two met on High Street outside of a recording studio in Wales while Gallagher was working on Definitely Maybe and Squire was in the middle of Second Coming, and before a 16-year-old Gallagher went to see Stone Roses and set his mind on starting a band — there was the Beatles, mod music, and Merseybeat. The regional British sound the Beatles built from Liverpool, later deemed Merseybeat, originated in part from city’s the transatlantic port which brought Buddy Holly, Elvis, Little Richard, and the like into their English experience. It was melodic, guitar-based, with vocals that teetered from McCartney’s wide range to Lennon’s contrasting voice, one “full of pain,” as described by Brian Wilson. They sang about their locale, and British life. They went to America in ’64, allegedly smoked weed with Bob Dylan, had their minds expanded, and entered the realm of prog, folk rock, and psych music. The 1970s brought punk and glam into the mix, with Big Star, alongside mod holdovers like Badfinger and XTC.

From there, as the ’80s arrived, and in Manchester, the Smiths came to be with a new-wave sound, while others returned to the ’60s pop psychedelia and mod sounds, and the Stone Roses began leading the way in the iconic Madchester scene — with punchy pop hooks that held onto melody as a pivotal piece while exuding an effortless, casual rock star attitude. “I thought, ‘You know what? They dress like us. They’re not wearing leather jackets. They don’t look like the Cure. They’re wearing trainers and jeans, and they’re sort of dressing like us.’ I could relate to them,” recounts Gallagher, of his first time seeing the Roses. “The Smiths beforehand were all wearing blouses and beehive haircuts and stuff like that. I loved the Smiths, but they didn’t look like us. They looked like someone else.” Music became an option at that moment for Gallagher, and that experience gave way to what would become Oasis, not to mention opened the doors for the whole ’90s Britpop world, one of which the Gallagher brothers would reign.

The lengthy history above is more or less to point out that this is a story about context as much as it is about recontextualization. Sound and its sensibilities travel through time, remaining timeless by how the artists and subcultures of each generation infuse relevant meaning into the music. The folky, prog sound of Bob Dylan or the Byrds bleeds into the baroque undertones of Rubber Soul, a sound which not only influenced Pet Sounds but permeated the pop and psych-rock movements that would define and redefine English music, regional and otherwise, for decades to come.

Though, in a piece for NME, Sean O’Hagan mentions, “There is a particularly credible music biz rumour-come theory that certain Northern towns — Manchester being the prime example — have had their water supply treated with small doses of mind-expanding chemicals.” I was curious to ask the two Mancurians in front of me, what, exactly, it is about Manchester that has produced such legendary musicians.

“In my experience, it’s to do with the success of bands that go before you,” Squire says. “With the Smiths, we used to rehearse in a room next to Johnny Marr, and he had a drummer that I went to school with, who was in the first band I was in when I was about 14. His drum kit consisted of cardboard boxes and suitcases. He was playing with Johnny Marr before Morrissey joined, and when I saw them take off, it made me think that you didn’t have to be from London to make it. I wonder if that plays into the equation — if you grow up in this area and you see people making it. I know that happened for Liam. He saw us and thought, ‘I could do that.’” He continues, “I think it is more to do with that than the weather or the architecture or the industrial heritage. I think there were a lot of great bands from a lot of different cities.”

Of course, in following up with Gallagher, who I speak to on a different line, I get a cheeky answer that does blame the rain, in part. “I didn’t want to be in a band when I was young. When I was 5 or 6, I just wanted to do what 5- or 6-year-olds do,” he says, bluntly. “When you get to about 16, 17, 18, you realize that the city that we’re born in, there’s been some great bands come from there. The Beatles from Liverpool, there’s been Joy Division, the Hollies, Bee Gees, the Smiths, and Buzzcocks. There’s lots of musical history in that thing. So you sit there and you go, ‘Well, if I am going to be in a band, then it better be a fucking good one.’” It’s a Liam-ism we can’t argue with.

“Plus, my theory is that it rains a lot in Manchester, and there’s nothing much to do. Well, there wasn’t when we were growing up, so the next thing was to play football, but then when drugs get involved, you can’t really play. You’re drinking and taking drugs, and that goes out the window. So the next best gig is, ‘Ah, where can I drink and take drugs?’ And they go, ‘Be in a band.’ That seemed to work… And, really, I joined the band to get out of Manchester and have a jolly. The only way out really was to fucking make it as in the band, you know what I mean? Digging holes was only going to get you up the road. So another fucking hole. So the band thing was the only way really to make it.”

Whether needing shelter from the rain, a way out, or it’s really in the water, the idea of the bands that came before being the ultimate catalyst stands out. To that point, there’s something to be said about the bands that come after, that can prove equally inspired. Billy Preston, playing keyboard with Little Richard, caught the attention of the Beatles, who were deeply influenced by both musicians. Later, they would come to bring Preston on for the Get Back sessions, and give him the only co-credit on a Beatles label project. While Gallagher discloses that he grew up with a poster of Squire on his wall, whom he totes as “the greatest guitarist of his generation,” the same could be said for Squire, in a proverbial sense. The guitarist gushes, “I’ve often fantasized about working with Liam and thought it could be really good.” And when given the opportunity to, he continues, “I was super excited about it, literally living the dream, not to be sarcastic.”

They first took the stage together at Knebworth in 1996, with Britpop at its peak and Oasis at the crest of their second album’s wave, headlining the festival before a record-breaking crowd of 250,000 people. In a moment of awe for both Gallagher and his brother Noel, their hero John Squire joined them for their hit “Champagne Supernova.” Legend has it neither brother has much memory of the night, but luckily for Gallagher, there was another chance. Following Oasis’ split, Gallagher embarked on a solo career, releasing new, original songs while also playing Oasis tracks live. At Knebworth in 2022, Gallagher made his second headlining appearance, and though Noel wasn’t beside him — Squire was, not only to play “Champagne Supernova” again, but to make his performance debut after five years, and his injury.

Arguably, that set could be considered record-breaking as well — for the sole reason that it has led us to Liam Gallagher John Squire, bringing two musicians from being a part of lionized bands back into the collaborative realm. Gallagher is also quick to tell me that he wasn’t planning on partnering up again. “I was quite happy just doing what I was doing, on the solo thing, you know what I mean? Obviously, that was keeping me out of trouble.” He goes on: “Then John mentioned when he would come down to rehearse for the Knebworth thing. I hadn’t seen him for ages, and I went just kind of flippantly like, ‘What have you been up to?’ And he’s gone, ‘Oh, I’ve been writing some songs.’ I was like, ‘Oh, nice. I hope there’s lots of guitars on it?’ And he went, ‘Yeah, man.’ I said, ‘Who’s singing it then?’”

In part dry British delivery, in larger part that general Gallagher lackadaisical, forward attitude, he caps the story with, “It was just that blasé. We didn’t sit down and make a big plan about doing stuff. It just happened.” And in listening to the 10-track project, that is believable. It’s certainly not simple or lacking depth, but it feels very true to each of them, and perhaps given the longstanding influence of Squire’s Madchester roots on Gallagher’s Britpop style, they fit together seamlessly. With Squire on songwriting and guitar parts, and Gallagher on vocal duties, they are focused on understanding the assignment, and keeping it at that. That said, it’s an assignment they understand like no one else. “John likes the same kind of music as I do, so it felt normal and right. I don’t like doing things that are going to bring me out in hives. That’ll stress me out. I’m too old for that now,” Gallagher explains. “Not like it was easy, but like to be in a comfort zone. I’m not into this, ‘Hey, man, it gets me out of comfort zone.’ Fuck that. I like to be comfortable now. I’ve had too many uncomfortable zones.”

What keeps this album fresh is that brilliant recontextualization. Taking that mod sound that’s traveled from the ’60s to the ’80s to the ’90s to today, Liam Gallagher John Squire is nostalgic for a time when music gave melodies the stage, and left room for lead guitars, while incorporating the pop genius of producer Greg Kurstin (Adele, Foo Fighters) that adds a new level of roundedness and amplification. However much we can hear the time warp in certain notes, or feel the 20th century, a Beatles influence, or a bit of Badfinger in there, the fact remains that we got this “crucial, spiritual” piece of music in 2024, and thereby it’s something incredibly new, and incredibly important.

From the opening track “Raise Your Hands,” we’re reminded that the music scenes each of these men came out of were a reaction to grunge, and the darker, lower energy sounds of coinciding with their own rise to fame. Squire and Gallagher are in the business of upbeat psychedelia, of relaying a message, the meaning of which we might not fully grasp, that is hopeful, energetic, and has a sense of humor. “I can see you, we’re alive!” Gallagher sings on the hook, his voice going from signature gruffness to smooth and strong, while Squire’s guitars wrap around the words, with goosebumps-inspiring fluidity. On “Mars to Liverpool,” we get a pure pop crescendo, the band’s impeccably cohesive sounds coming together, held by steady symbols and a tactile bassline, walking alongside trippier psych riffs, and Gallagher lolling the abstracted lyrics. Across the album, they continue to weave in and out of bluesy arenas (“I’m a Wheel”), touch on classic rock beats (“You’re Not the Only One”), and drawing on prog and folksier sounds (“One Day at a Time”). While there are a multitude of throughlines, sonically, including the obvious vocals and guitar, the lyrics are also a feat to unpack. And apparently we aren’t supposed to even try.

“I think sometimes when songwriters get asked to say, what’s that about? And then they go, ‘Oh, it’s about this.’ I think it stops the imagination [from] listening. Whereas if they don’t tell them what they’re about, it is endless. It’s infinity,” Gallagher tells me, as I broach the subject of Squire’s lyrics, and his trust in them. “The thing is it’s like in 20 years’ time, it’s all about the feeling, isn’t it?” After a minute, he continues, “Well, John’s a painter, isn’t he? And he does a lot of painting, so he lives a life in color. Whereas maybe some of us live it in black and white. So there’s lots of that going on. I mean, I haven’t got a clue what they’re about. And I actually don’t want to know, you know what I mean? Because I just feel they feel right to sing.”

I called Squire separately from Gallagher, and unsurprisingly, I immediately recognized the two operate at drastically different speeds. Gallagher and I talked about drugs, football, and the album — and with Squire, our conversation wandered from the music into talks of touching grass and The Artist’s Way. That being said, we also talked about his art, which ranges from painting and sculpture to welding, and the colorful, bold pop art, which is featured on the cover of their new album. The art, I point out, is not unlike the music it’s enveloping — vivid, abstract, open to interpretation. “You’re onto something with that. I agree. We did a round of interviews in Paris last week, and some of the journalists were probing for meaning and explanations,” Squire replies. “I ended up with this term — that it’s like a ‘collage of lyrics.’ It’s not one theme start to finish for most of the songs.”

![G-S_0879-RGB-[Photo-Credit_Tom-Oxley]](https://www.altpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/12/G-S_0879-RGB-Photo-Credit_Tom-Oxley.jpg)

Squire hasn’t ever subscribed to the need to give lyrics an explanation. “I got a Clash songbook when I was 14 and realized that I was singing the wrong words, so for a few weeks, I resented the band for changing the song. I’ve reflected on that from time to time, and I think that it’s the listener’s prerogative to decide what the song means to them.” I probe him about his favorite song on the album, to which he answers the last song on the album, “Mother Nature’s Song,” the track that also triggers Gallagher’s emotional side. “It came so easily,” Squire says.

When it comes to his songwriting practice, and this cherished track, Squire sunk his teeth into the idea of earthing, or grounding. “It’s a theory that if you walk barefoot on anything but tarmac or concrete, then you get the charge in your body realigned, the ions in your body. Part of the theory is that we weren’t designed to wear shoes and taking them off is good for your mental state.” The products that have emerged from this line of thought can give you the same effect while at your desk, or around the house. “I bought a little mat to put on a chair that I sit on when I’m playing guitar, and the first time I tried it, that song just seemed to come out of nowhere.” Though Squire eagerly shared this, as our interview ends, he asks for an addendum: “Please don’t go big on the [earthing], because it’s a bit of a foil hat… But it did work for me. You never know.”

As to writing, art, or music, in whatever capacity — what these two men share above all else is an “urge.” As Squire puts it, it’s this urge that leads to art, writing, and music. Gallagher explains, “We’re not doing [the album] to make money or be more famous. I mean, we’ve got all that. We’re just doing it for the love of music, and I think that comes through in the record.” He excitedly continues, “If we inspire people to go and join a band, that’s what it’s all about. Even if it’s like one person will do, know what I mean? It might just kick-start something, and it might not.” Back to the X post, it seems that harnessing that urge is how music crosses over into becoming crucial — for the artist as much as the audience.

“The journey is the trip I say,” Gallagher croons on “Mars to Liverpool.” The same can be said of Liam Gallagher John Squire. There was no plan. It just unfolded, in real time. Guts were followed, dreams were fulfilled, egos grappled with and shed. And as an audience, we are returned to a time and place that’s familiar and nostalgic, yet reborn each decade or so with a new air about it. We’re reconnected with melody, introduced to the power of a guitar again, and reminded of the way one voice can take charge of our emotions. Squire said it best, and I’ll echo the sentiment: “There’s something different about this record. I don’t know what it is, but I can keep going back to it, and I know it inside out, but it still moves me.”