If Robert Johnson had lived long enough to play John Hammond’s Spirituals to Swing concert in Carnegie Hall in 1938, renowned musicologist Scott Ainslie thinks we would have had rock and roll 10 years earlier than we did.

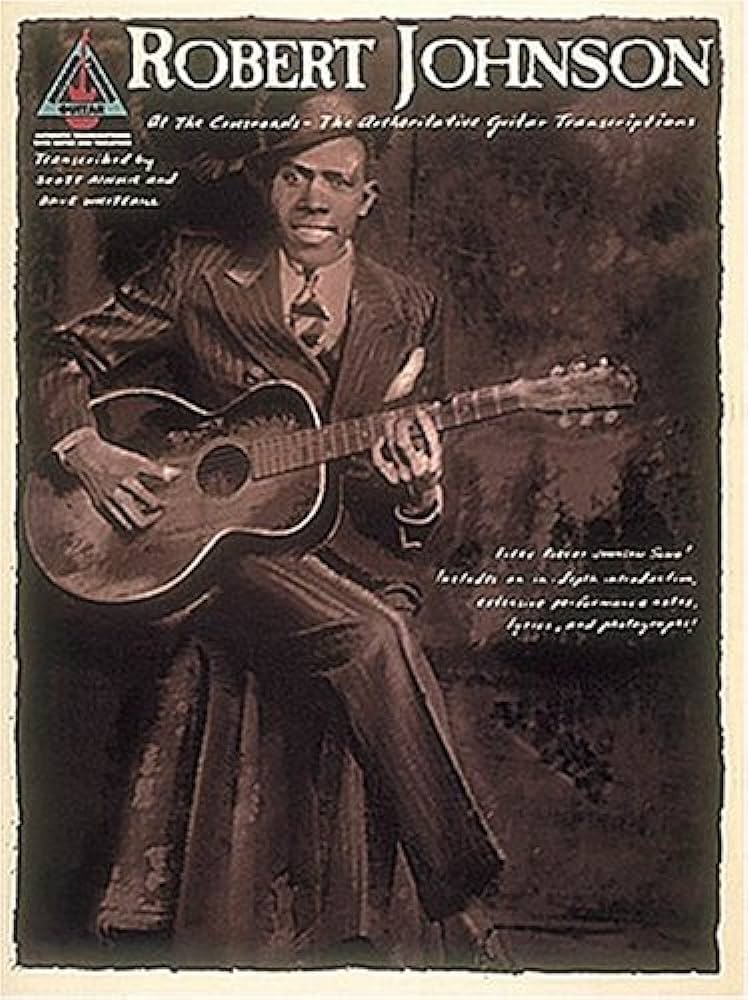

“I think he would have bought a new tie,” says the man who wrote the definitive book on Johnson, Robert Johnson/At The Crossroads, containing transcriptions of Johnson’s recordings with annotated lyrics and historical notes. “That concert made Bill Broonzy’s career. Broonzy replaced Johnson on the bill.

“You put an electric guitar in Robert’s hands with bass and drums? Lord, have mercy! Things would have changed in a crazy way. The thing about Robert’s recordings and the things he did, he had one foot in the old world! Until he was 16 in 1927, every bit of that music that Robert heard would have been played by someone in front of him, and there were recordings of solo acoustic blues available or even made before 1927 when electronic microphones were invented.

“When you bring the microphone to the guy instead of the guy in the studio, the whole world opened up. Until Robert Johnson was 16, the only people he heard play music in his community – from 1927 on, until he did records – became part of Robert’s oral tradition as they are part of ours.”

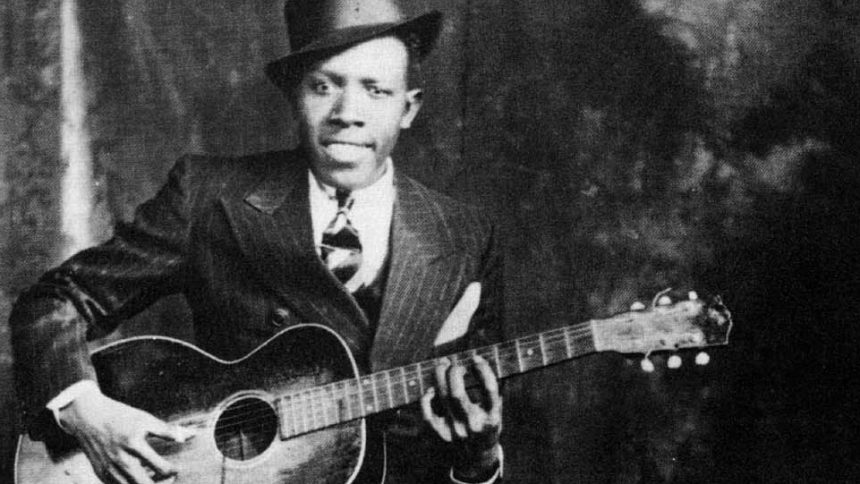

Today, Robert Johnson remains the least well-documented of any bluesman and yet his recordings are like The Old Testament of the blues Bible.

“This was an ambitious musician who was aggressively curious about music, did not want to walk around in fields, and was just fighting his way out of the sharecropping system with his own kind of musical talent. All that stuff holds up perfectly, and it’s in the grooves there in the recordings, but it’s fun to have the other information.

“He played everything he could play, and there are stories from musicians that toured with him – Johnny Shines, Robert Lockwood and one or two of the old girlfriends that Robert would hear and sing while you were talking to him somewhere. Somebody would play a record, and later in the afternoon he would play you the whole song, words and everything. Just play it the first time. Hear it the first time and just play it.

“He was an incredibly facile fellow, and he apparently wanted to hide who he was. He didn’t want to be known. So, he would just walk out of the gig ’cause you were watching his fingers too closely. These guys were protective of what they were working on, and Robert was like that, too. And nobody ever remembers hearing him practice and watching him working on something. He was as I say just an incredibly facile and ambitious young man, and it’s a beautiful thing to let him be humanized and the Godhead of Delta blues.

“The biggest seller of Robert’s was like 5000 records. At the same time, some of the other acts were selling 30,000 records (like Leroy Carr and Blind Blake) and riding around in cars. Robert never had a car. Robert was a walking musician. He walked, hitchhiked, and hoboed the train to get where he wanted to go.”

His market was almost 100% African American. “He played everything that was current. All those early guys in 1927 when Jimmy Rogers started recording. My God, these guys loved that shit, but they wouldn’t let him record it, and so we only get a recorded version of the live old blues, but they played everything. And they liked everything.

“Anything that was good they played, and the racism of the recording industry is what makes us think a real blues guy is only going to play blues. They’re not going to play anything else. Modern performers like me are kind of straitjacketed into that thing. You’re not a blues guy because you played a Van Morrison song. You played a Billie Holiday song. This is what musicians do. You play what’s good.”

Scott Ainslie is a Phi Beta Kappa graduate of Washington & Lee University. More importantly, he plays guitar with a passion and intensity that practically raises Robert Johnson from the dead. “My allegiance is to the sound we make. So, if you played something black, white, yellow or brown, that I think is cool. How did you do that? What was that? And all of us, all musicians are like that. The music business is racist as all hell. The society? My God, we can’t apologize enough, but among musicians between you and I, it’s like ‘that’s great! How did you do that?’ The color barriers did not work.”

Scott got a call just after the pandemic from Annye Anderson, Robert Johnson’s stepsister who lives just south of him in Massachusetts. “She’s 91 or something. She’s a powerhouse, and she wrote a book called Brother Robert: Growing Up with Robert Johnson.”

“There’s some factual things in there that probably aren’t right, but there is a phenomenal amount of inside information about being 19 years old and having Robert Johnson as a step uncle and his coming around the house.”

“I had a chance to visit with Annye in her apartment 10 feet apart (during the pandemic), and she gave me a copy of her book, and I gave her a copy of mine. And she gave me a quart of barbecue sauce which I haven’t opened yet. I’m waiting for a special occasion. She said this was her favorite barbecue sauce, and I can tell you everything that’s in it, and you would never make it like this.

“She’s a firecracker. Anyway, a lot of facts came to life. We have a lot more information now than we did then, although whatever I wrote in this biography for the Johnson book, the introduction for that book of transcriptions is holding up pretty well.”

Scott Ainsley is a traditional musician with expertise in Piedmont and Delta Blues as well as Southern Appalachian fiddle and banjo traditions. He’s a public Fellow at UNC-Chapel Hill. He’s earned grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and The Folklife Section of the North Carolina Arts Council. He’s studied with elder musicians on both sides of the color line – in the Old-Time Southern Appalachian fiddle and banjo traditions, as well as Black Gospel and Blues. and specializes in performing and presenting programs on the European and African roots of American music and culture in community and educational settings.